WHENEVER I see on a map the words, Developmental Road, it always grabs my attention for being a less-used route.

Apparently the name Developmental comes from the roads being under constant development, and a lot are damaged or washed away from the severe wet seasons in the north of Australia. The facts are that they are always gravel, are variable in their conditions, and were originally built to facilitate the transport of stock in the far reaches of Queensland.

Spending time at Karumba on the southeast coast of the Gulf of Carpentaria and looking for an alternative route across to the east coast of Queensland, I spied the Burke Developmental Road (BDR). Karumba’s a bit of a strange town as, if you’re not a fisherman, there’s honestly not a lot to do.

Located right on the banks of the Normanton River, the waters are apparently rich with barramundi and Gulf banana prawns which are the town’s main industries. After visiting the Barramundi Discovery Centre where you can learn the history and behaviour of the barra and other aspects of the town, you can dine at the sunset bar which is one of the few places in Queensland where you can watch a sunset over the ocean – but that’s about it for Karumba.

A working town, Karumba is an industrial port for the specialised barra and prawn fishing boats, for where livestock gets loaded, and where MMG Century mines has a loading facility for its 300km underground pipeline to exit from where it conveys zinc slurry from its mine to the west. Just offshore, Sweers Island is a paradise for anglers, surrounded by reefs and holding a ton of sportsfish – it was named back in 1802 by Matthew Flinders.

One interesting fact about this area is that it has only two tides (not four, like others) in most 24-hour periods, This is due to the narrow waterway at the top of the Gulf, where water surges push against each other and stop the flow.

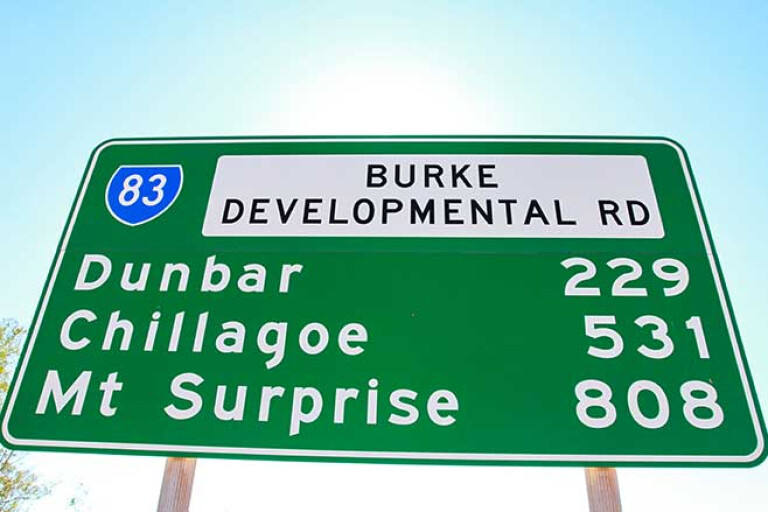

The BDR caught my eye for several reasons: it was a long way between fuel stops, which meant it was less-travelled by others; and it runs along several rivers for a few miles, so is hopefully good for remote camping. Leaving Karumba, it’s a sealed road to the start of the BDR (or, on some maps, the Normanton-Dimbulah Road) just 41km away, and right from the start there are warning signs regarding no fuel for 600km and rough roads.

The BDR heads in a northeast direction for nearly 260km, passing through open savannah plains and woodlands. At the time we travelled on it there were also about four million corrugations, which definitely found new rattles in the old Cruiser.

VAN ROOK STATION

ABOUT 100km into the trip there’s signage for Van Rook Station. Now, while it’s not possible to enter the gates, this empire consists of more than 1,000,000 hectares of prime grazing land broken into four different stations dating back to 1883. The Dutch-bearing name Van Rook refers to early coastal explorers who sailed past the top of Australia in the 1600s.

The station runs approximately 100,000 head of Brahman cattle, and one outstation is surrounded by water on three sides. Plus, some outstations have fresh waterholes nearly 20km long, while another is bordered by remote shell-covered beaches. Van Rook is regarded as the largest station in Queensland.

This section of the BDR runs diagonally with the gulf coastline for 260km, with several massive bridges across rivers flowing into the gulf. Being only 100km to the coastline, there’s always a good chance to see a few crocs along the way if there’s any water in these rivers. They may only be freshies, but be croc-wise.

DROP THE PRESSURE: Here's why you need to drop PSI

It’s not long before the BDR takes a sharp turn to the right and starts heading directly east along the Mitchell River at Dunbar Station. The landscape seems to change where there’s more moisture in the ground; the trees are greener and the low scrub thicker. Our camp for the night was at the Drumduff Crossing on the banks of the Mitchell River.

The crossing over the water is a long, low concrete causeway which acts like a weir holding back water on one side, yet the water can cascade over when there’s flow. What blew me away was that the causeway is just 200m across, but during the wet season the river is nearly 2km wide – this was apparent by the amount of sand the road traversed out the other side towards Drumduff Station.

This is one of those camps where you plan for one night and stay a few more. Just a stunning place where the serenity pulls you in, the water is cool on a warm day and the birdlife is amazing. Recent reports said that barra were caught upstream of the causeway, but unfortunately none were spotted or hooked during our stay. We did, however, see several small freshwater crocs away from the camp and at night it was possible to see their beady, red eyes glow from the torch beams. Swimming during the day was pretty safe in the shallow rockpools near the river’s edge.

CROC CULLLING: Is it necessary?

East of Drumduff the BDR starts to change, with mountains in the distance giving life to the barren landscape left behind. Waterholes filled with lily pads and alive with birdlife are an indication there is life out here still. Brolgas, wrens, jabirus and even ibis congregate around the water’s edge, looking for a feed.

Crossing the Lynd and the Walsh Rivers are other stopovers to look for crocs if there is any water flow, but nothing can be guaranteed at the end of the dry season. The road soon swings south and heads towards the Sentinel Range, where towering peaks seem to pop-up out of nowhere, but this volcanic area has been weathering away for more than 400 million years.

CAVING

THE Chillagoe-Mungana Caves National Park is known worldwide for its ancient aboriginal artwork, nearby heritage, and an estimated 600 to 1000 stunning limestone caves within the park. Luckily there are a handful that are easy to access, and you’ll be blown away with what nature has created. One of the better ones is 30km before Chillagoe in the Mungana Reserve, named The Archways.

A labyrinth of caves and walkways are spellbinding, with tall trees shooting skyward and stretching out above for any moisture in the air. It’s an amazing walk through the different rooms exploring the rock formations and cosy caves. Outside there’s the Mungana Rock Art site, where a host of ancient Aboriginal paintings depict a story from years ago in a peaceful area.

In conjunction with volcanic rock, minerals are normally found nearby, and within a few kilometres towards Chillagoe is the turnoff to the Mungana historical mine that soon caught our attention. An easy road in, it stops at the once rich and rough town site of Mungana, where way back in 1896 copper was found.

With a smelter and railway line back to Chillagoe, the town was set up here but it was a harsh area with a lack of water, facilities and food plaguing the workers for many years. Walking around where the town once was beside the railhead, there’s evidence of buildings and a few relics; the railway line is still there with uneven sleepers, and the info boards depict a picture of prosperity and hope.

Sadly in the early 1940s the OK Mine closed and the people blended into other areas within the district. Originally horses and camels were used around the mine, but the horses started to bolt and were erratic when the camels and cameleers came too close. Soon only camels were used to transport the copper from the mines, but during this time the animals were getting sick from eating the leaves off the ironwood tree.B

CAPE YORK: Best 4WD tracks in the Cape

However, a bit of smart thinking in 1907 by head cameleer Abdul Wade bought several steam-driven tractors in to move the heavy loads from the mines. At the peak of production there were 13 tractor engines operating and, when the mines closed, Japanese interests bought all but one of them. The last one was sent to Atherton where it was used to haul timber.

The last stretch of road to Chillagoe is sealed, and something not to be missed in town is the heritage-listed Chillagoe Smelter site. Huge amounts of copper were found here in the early 1880s and this subsequently opened up Far North Queensland for more mining exploration. At the peak of production, more than 1000 people were employed within the mines. However, in 1914 the mine shut for the duration of WWI and failed to reopen due to financial problems and overcapitalisation of the mine.

Over the next few years the Queensland government took ownership and recommenced operations, trying to help it through the depression years. However, it failed and the smelters closed once and for all. Today the site has been cleaned up and there are public viewing areas that overlook the chimneys, the main smelter area, tunnels and more.

Walking tracks lead you to where the manager’s grand house once stood overlooking the stunning Featherbed Ranges to the east. Another walking trail takes you to a view of the largest remaining slag heap left in Queensland. After processing the ore, the leftover material (a thick liquid called slag) was transported by a trolley on rails with large bell pots on the side to the dump. It’s estimated that nearly a million tonnes of waste was dumped to make this slag pile.

There was a vision by John Moffat to create a network of railway lines, from the smaller mines back to the massive Chillagoe Smelter works, but reports of corruption, mismanagement and scandals soon brought everything to a halt. They say that the Chillagoe Smelter never made a profit in any year, only supported the town through a flow-on effect where there once were 10 hotels, a bustling town centre and relevant services. Today Chillagoe is a quaint drive through an outback town, where history blends in with the new.

The BDR continues on towards Dimbulah and is a mixture of dirt and sealed road. While the entire road can be done cautiously in a modern car, a 4WD is highly recommended due to the lack of road maintenance, wet-weather events smashing the area, or just finding those little out-of-the-way campsites. Listed as one of Australia’s most dangerous roads and at more than 1000km long, the Burke Developmental Road is anything but boring if you’re keen to heighten your sense of adventure.

COMMENTS