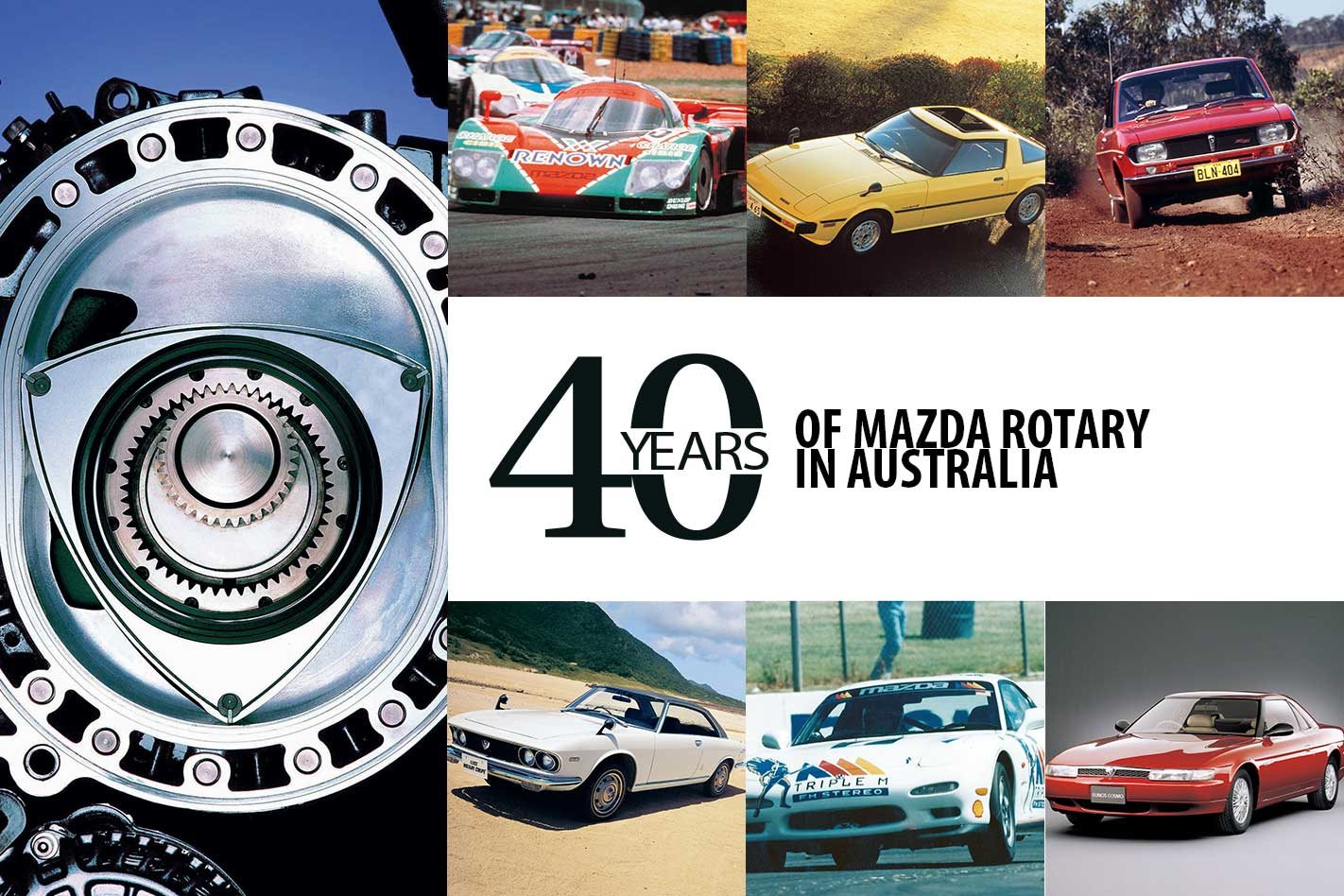

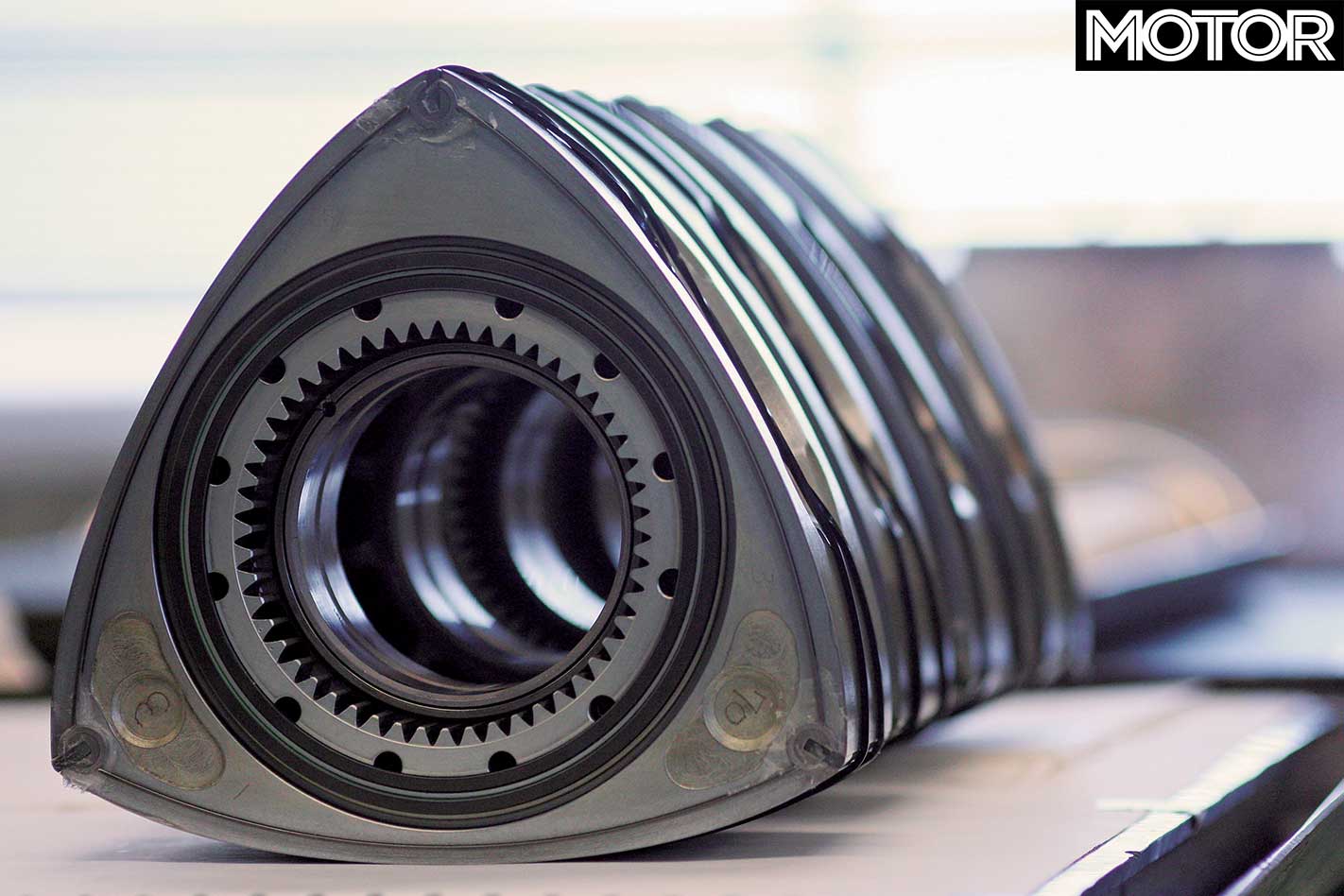

It’s unconventional, daftly simplistic and its disciples are fanatical. But after four decades in Australia, the spinning, screaming ‘Wankel’ rotary engine has carved its own niche courtesy of its only remaining supporter, Mazda.

This feature was first published in MOTOR magazine’s February 2009 issue.

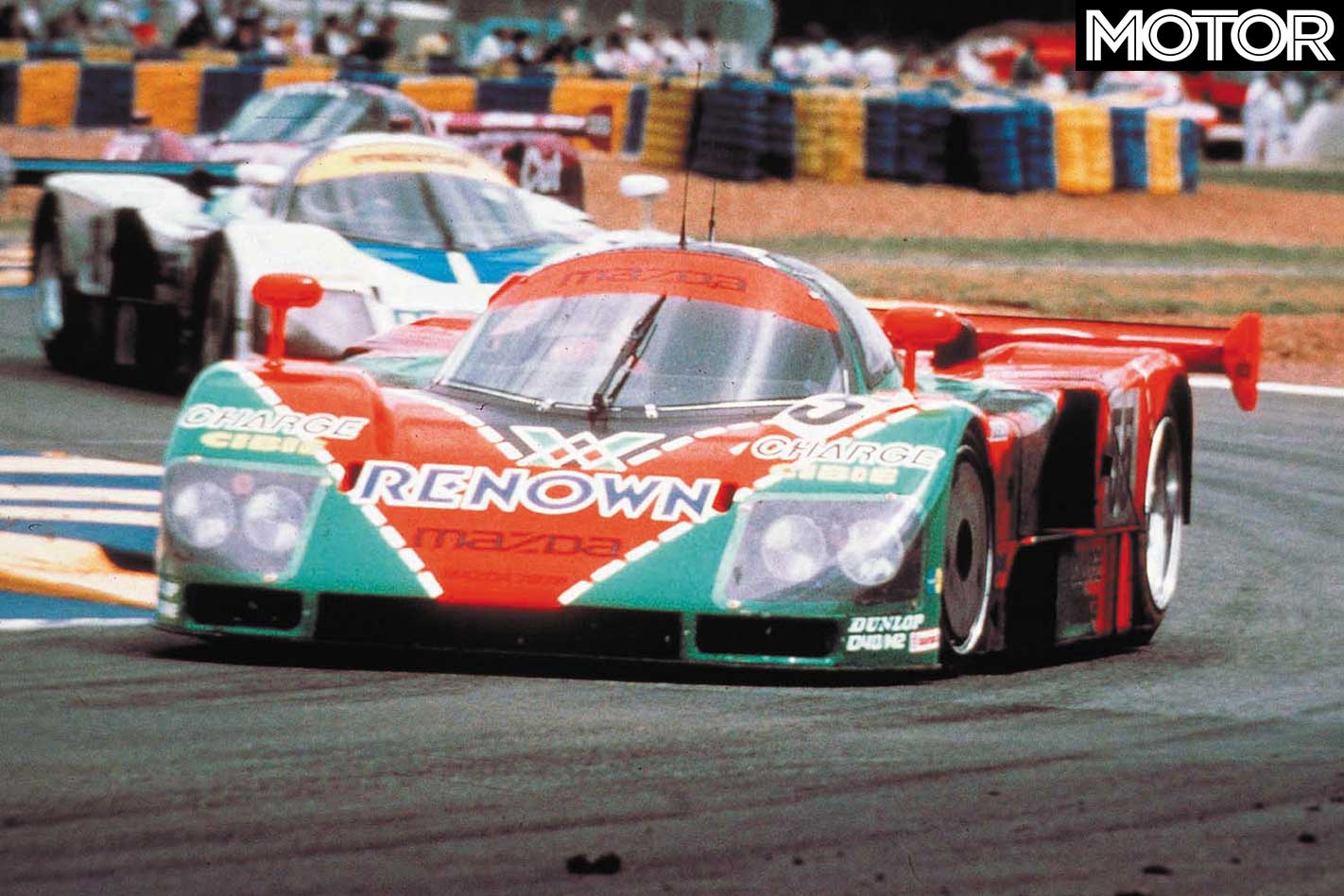

It has become a genuine performance and racing icon thanks to victory at Daytona, Le Mans and the Bathurst 12-hour, but in hindsight, it’s hard to believe the rotary has survived.

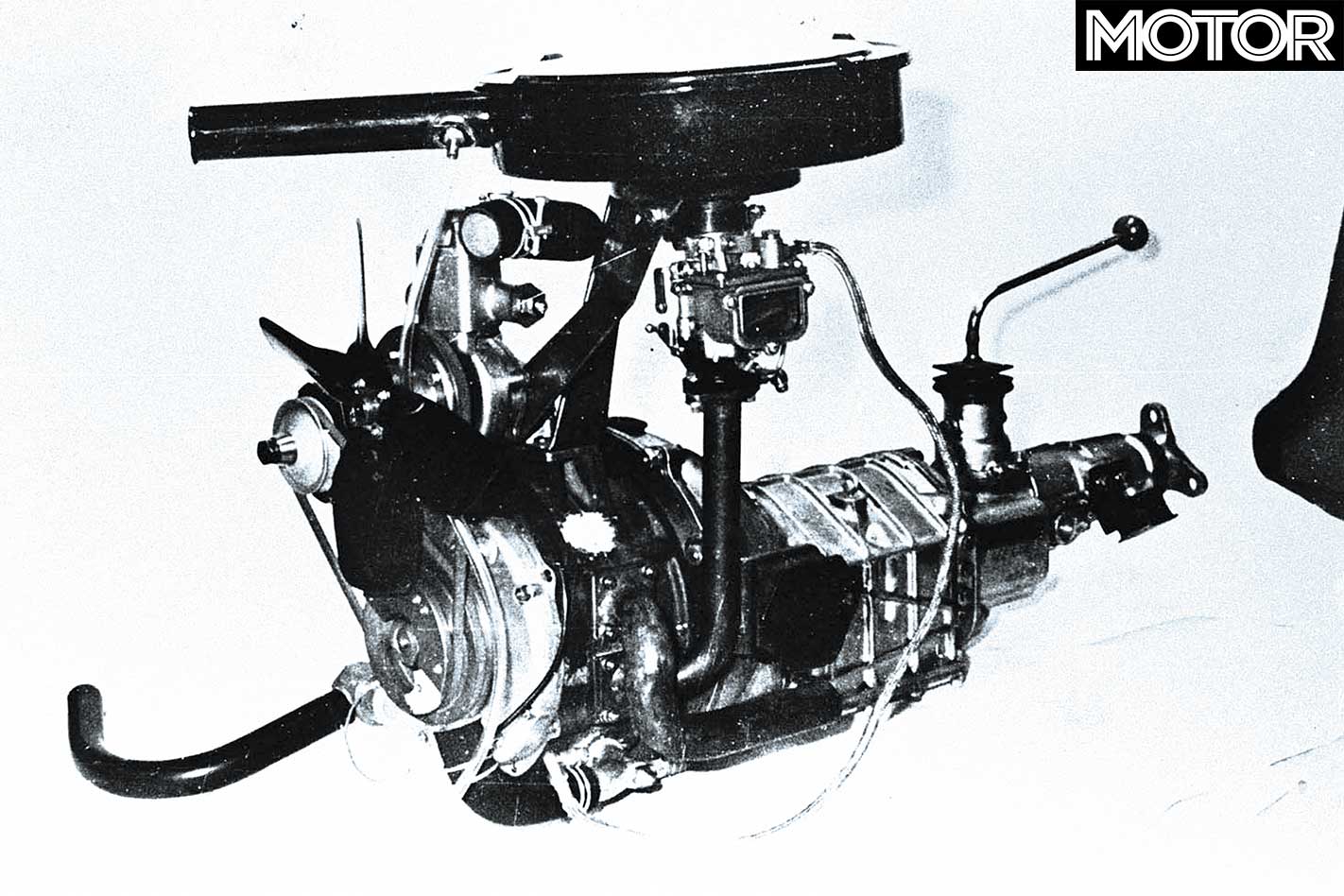

The R100 became the first ‘ordinary’ Mazda to feature a range-topping rotary variant, but while its engine and its performance both far exceeded expectation, its primitive chassis and narrow-track stance undermined its engine’s racetrack potential. The Cosmo had already proven the rotary’s suitability to racing – it finished fourth in the 1968 Nürburgring 84-hour endurance race – but the R100 wasn’t the right car to cement that reputation.

At the time, Mazda openly suggested that the rotary would one day render the piston engine redundant. So, in opposition to the Cosmo coupe’s purist sporting focus, it set about installing the engine across its entire mainstream range.

Next recipient was the medium-sized Capella RE (RX-2 overseas), which joined the R100 in 1970, and proved a far more sophisticated and suitable poster-child for rotary power. In December ’70, Modern MOTOR described it as “one of the most exciting cars to come our way in many years”, and pointed out that “the Wankel rotary engine is no longer a gimmick.”

The sentiment of the day was that the Wankel design must’ve surely been “the first serious line of writing on the wall for the conventional piston engine.” Or so people thought…

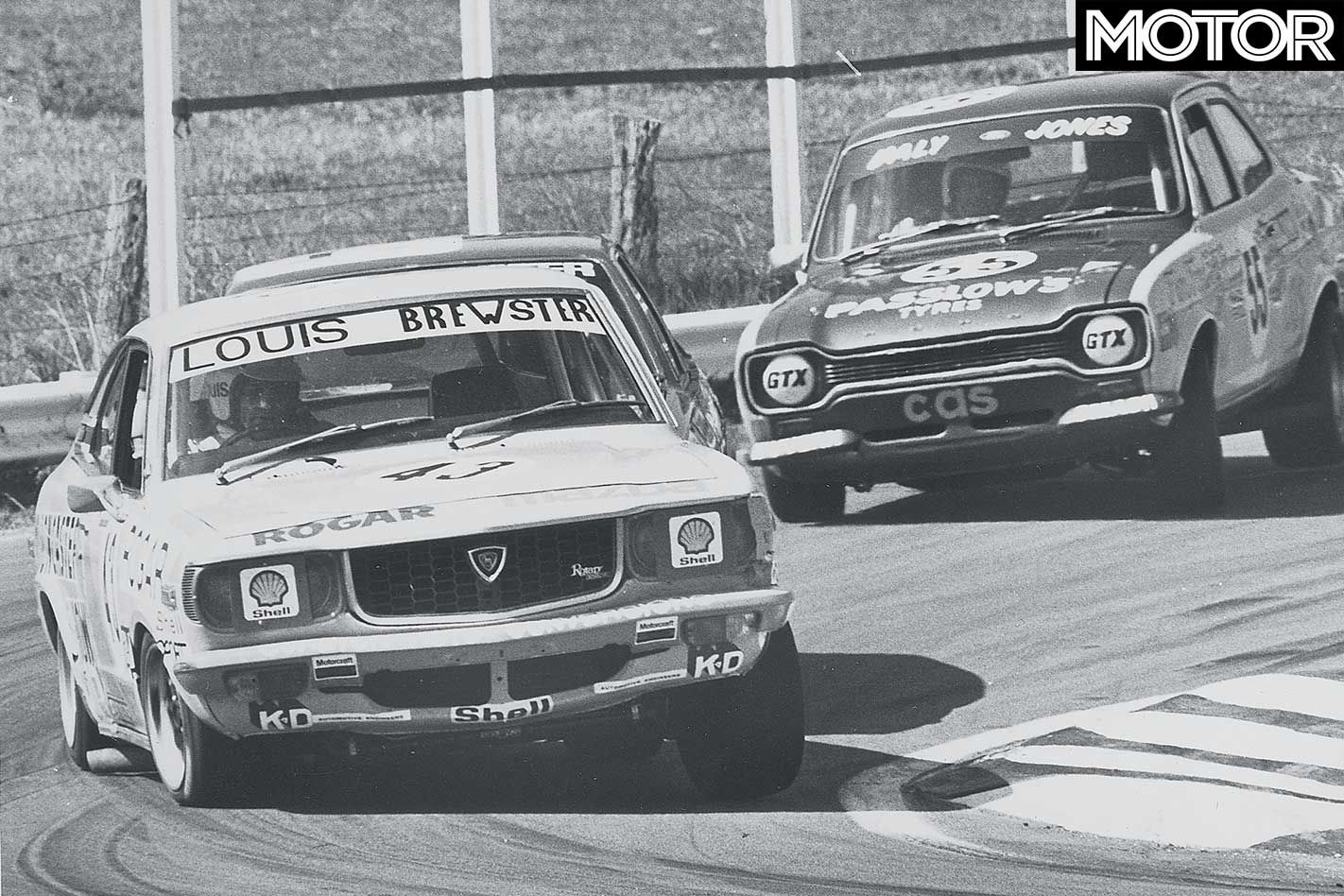

Nowhere was the rotary versus piston argument more volatile than on the racetrack. Wayne Rogerson raced a Capella RE at Bathurst in the early ’70s, winning his class in 1973, and still campaigns a rotary in historic racing.

“It was an effective little car and quick down the straights,” he explains. “We were doing 130mph [209km/h] down Conrod.”

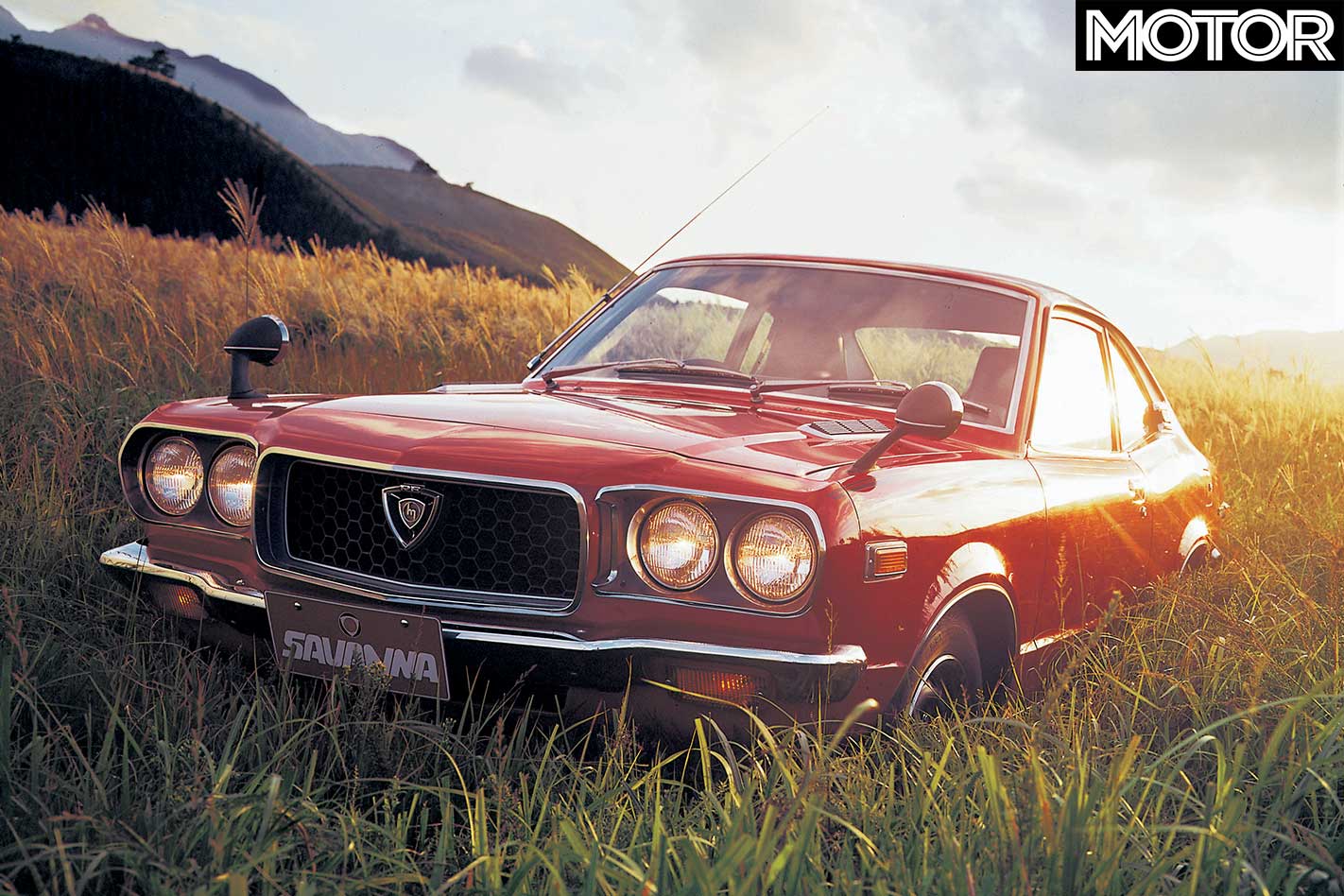

The R100’s effective replacement came in the form of the RX-3 in February ’72. It was a serious challenger to the Escort Twin Cam and Torana GTR, and was offered in both four-speed manual and three-speed auto forms, sedan and coupe. And it sold alongside the Capella RE, initially using the same 82kW/135Nm 10A as the R100 (but with a new housing and honeycomb exhaust ports to improve emissions), giving Mazda its widest range of rotary models to date.

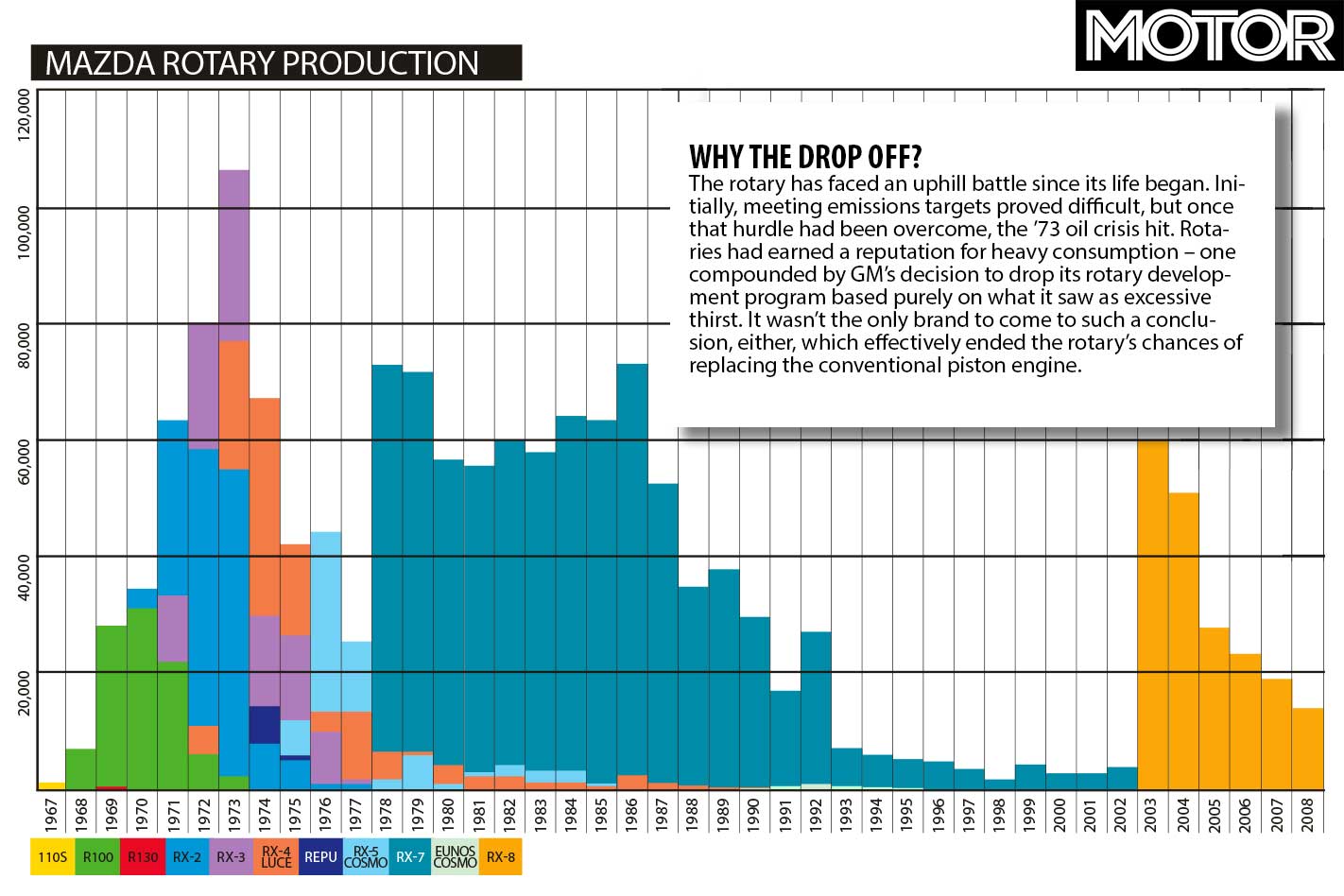

The RX-3’s introduction greatly boosted rotary sales, which by 1972 represented one-third of Mazda’s total engine production. The following year, Mazda built more than 100,000 rotaries, setting a record that still stands to this day, and Mazda Australia played its part – flogging an unbeaten 6218 rotary vehicles here. But from late-’73, the first oil crisis saw fuel prices skyrocket, and the relatively thirsty rotary took a big hit.

“[The RX-3] was a fairly well-balanced car and you could get all the performance options on it, like limited-slip diffs, a close-ratio gearbox and so on,” said Holland, who was also a Mazda dealer in Sydney. “We just thought that you run what you sell. The main Mazda sellers were the smaller cars, and we sold a lot of Capellas. People who wanted real performance would buy the rotaries.”

Holland’s RX-3 race car was stock, apart from the carburettor and some exhaust mods. “There was no porting modification,” Holland recalls. “CAMS wouldn’t let us use bridge-porting or change the RX-3’s induction. Peter Williamson was allowed to run a twin-cam Celica that was never actually sold here, but we weren’t allowed to port!

“Racing-wise, [the RX-3] was terrific, ’cause you could rev them all day. And we could use power and revs. It still had pace up top … it didn’t drop off like the Capri V6.”

The RX-4 was actually the first car − not just rotary − to meet the stringent new US and Japanese emissions laws, but the RX-5 had no claim to fame whatsoever, other than being fat and useless. In January ’77 we wrote: “In the company’s handout literature it states the rotary is here to stay and will eventually supersede all other methods of automotive power. That statement is just too grand and sweeping.” And so it proved.

While pollution laws could be met, the 1973 and 1979 oil crises had a profound effect – shrinking Holden’s Kingswood-replacement, allowing smaller fours to eat into the local brand’s market share, and forcing a paradigm shift in the rotary engine’s status. Its reputation for relatively high fuel consumption saw General Motors abort its aspirations for the engine’s widespread introduction, and Mazda’s rotary sales nose-dive.

While rotary-powered variants continued in the flagship Cosmo/Luce (929) line-up in Japan, the Japanese baulked at building a rotary-engined 323. The engine’s high-revving, constant-torque character lent itself to a dedicated sports-car application, not another basic small car. Enter the RX-7.

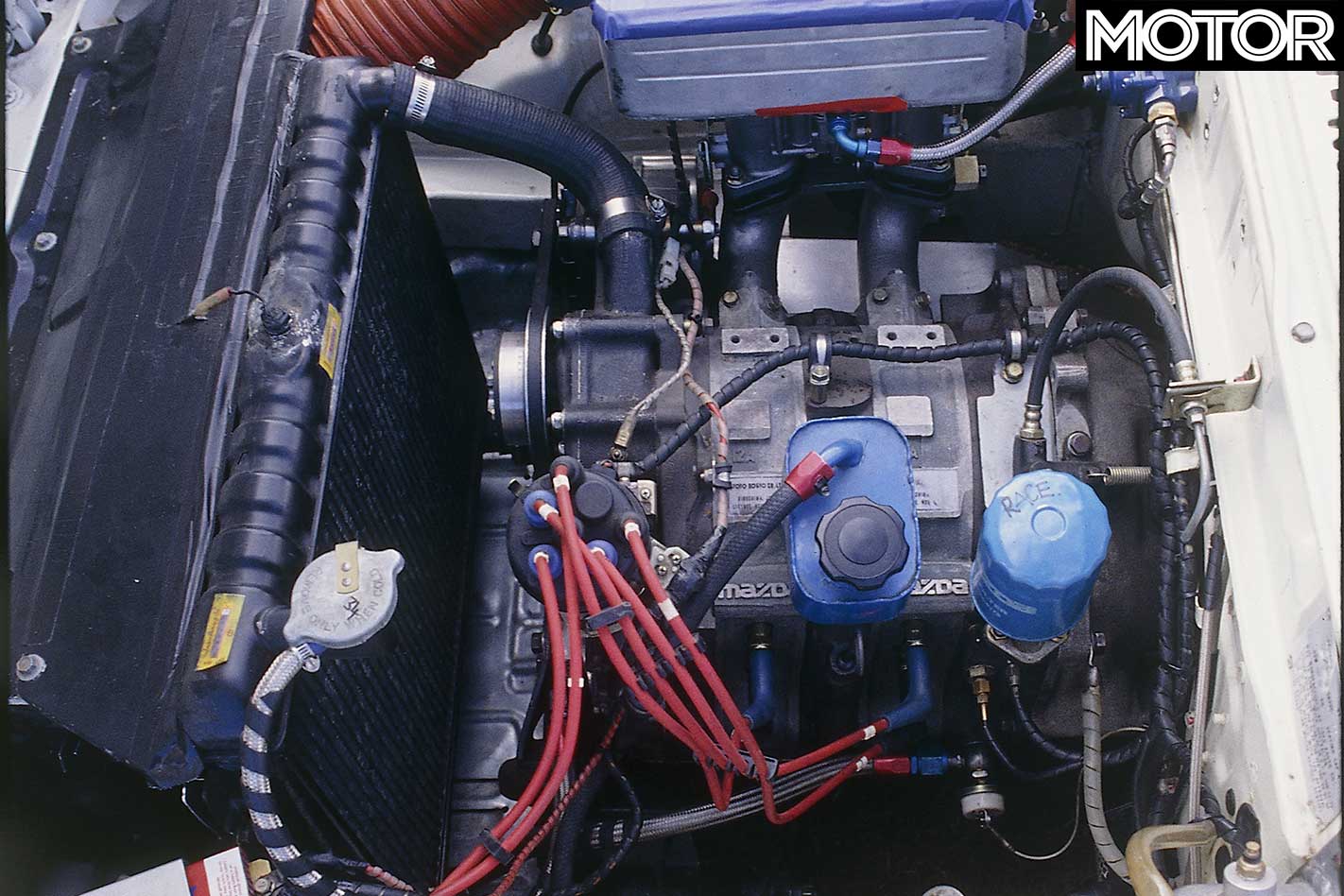

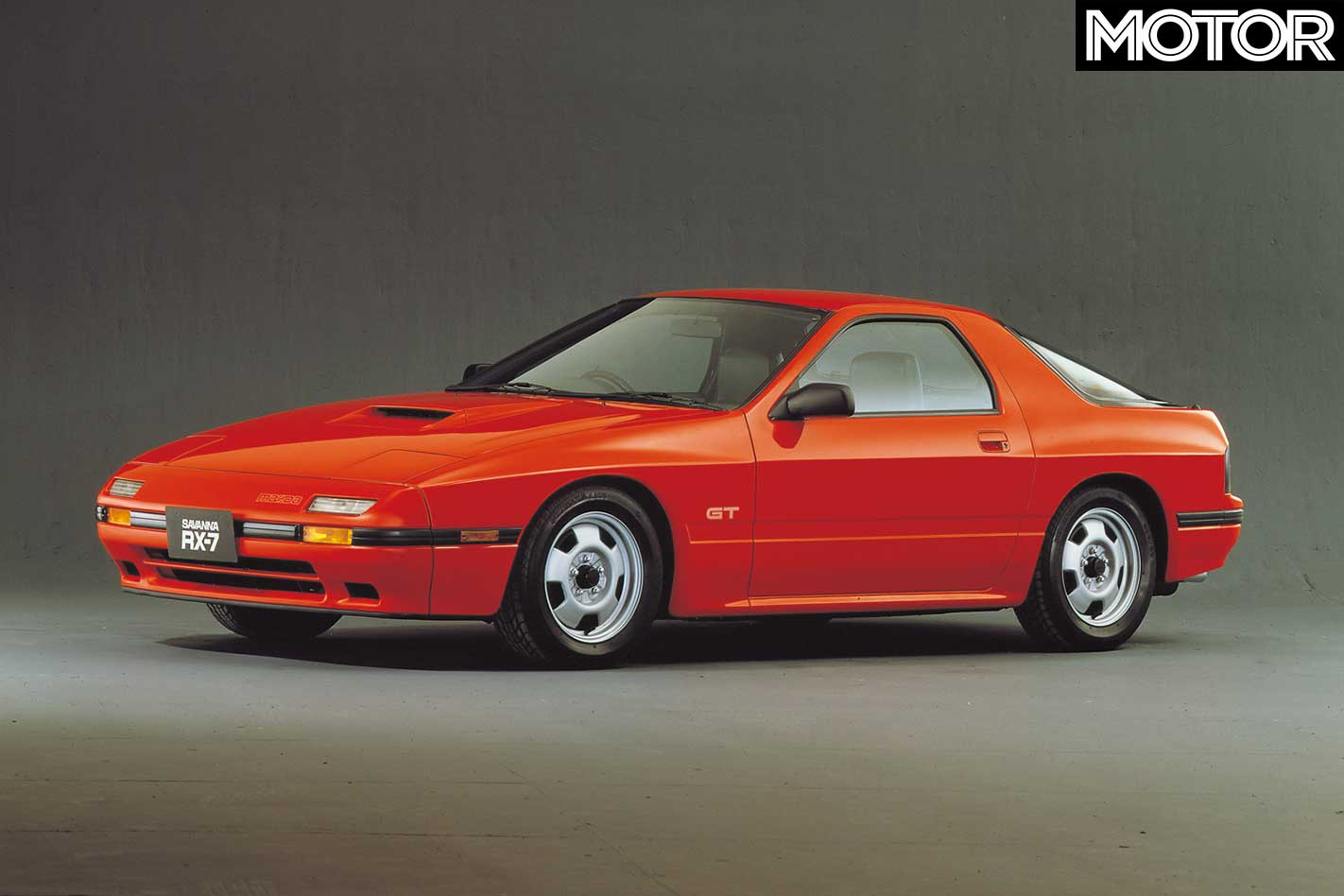

The Series I RX-7 arrived here in 1979, establishing itself as a serious performance device from the get-go, and demonstrating Mazda’s belief in the rotary, seemingly against all odds at the time. Engineer Takao Kijima, instrumental in every RX-7 and the iconic MX-5, studied the Porsche 924 to deliver a car that offered close to 50:50 weight distribution – achieved by locating the 12A in a front-mid position behind the axle line.

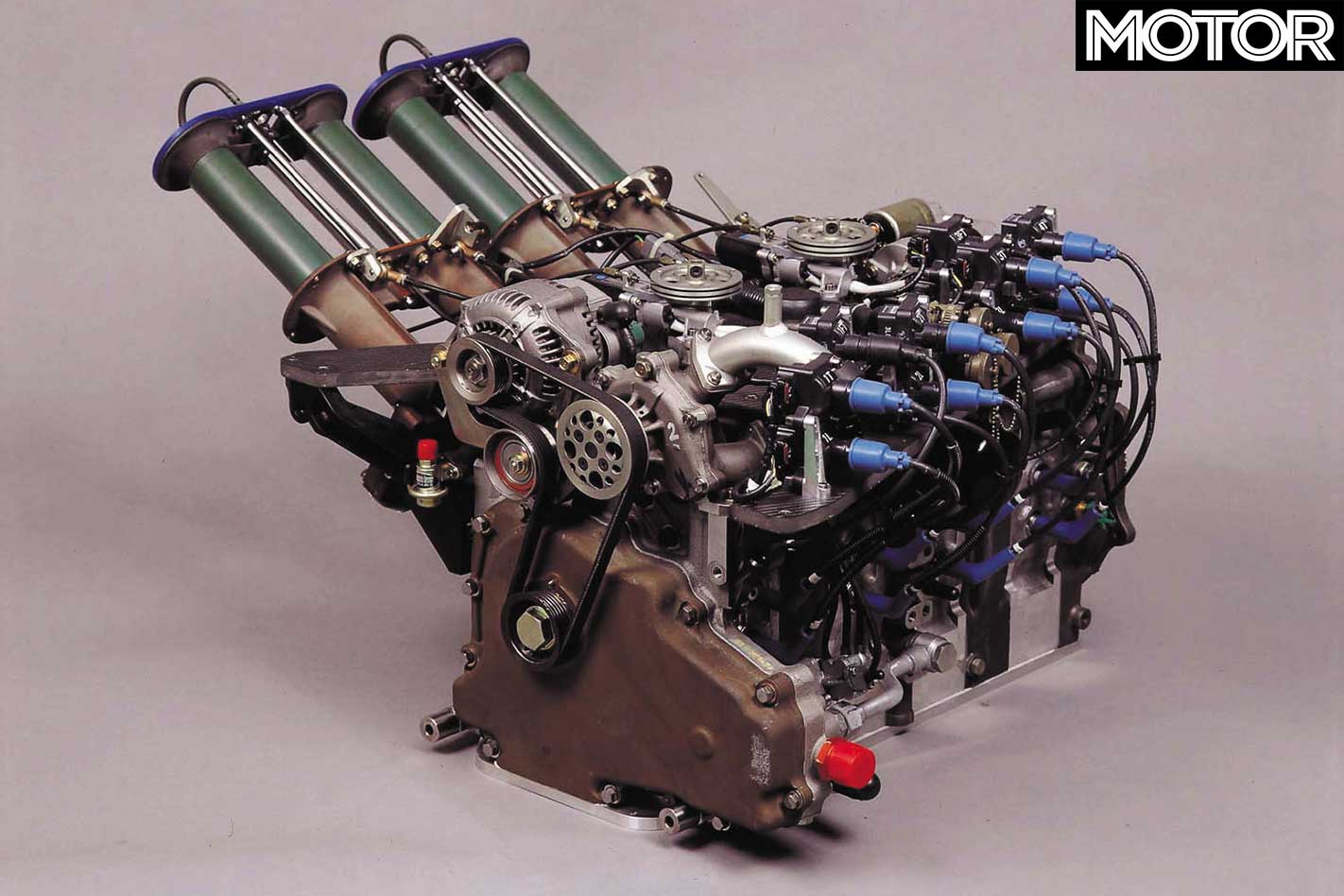

Racer Allan Moffat saw the RX-7 as his ticket to winning touring-car races − particularly Bathurst − after Ford pulled its funding from the iconic driver. But getting the car CAMS-approved with peripheral ports proved a nightmare.

How to police the rotary was one hurdle for CAMS; with no valves or camshafts, the 12A required no complex parts to produce more power, so induction modifications became the bone of contention.

“It was just magnificent; the pace of a rotary with a peripheral-port (over a bridge-port) is like driving a 1980 Commodore compared with today’s V8 Supercar. There were improvements in everything – power, torque, response – providing phenomenal pace.”

Opposition to Moffat’s campaign was heady, until Allan Horsley, the manager of Moffat’s Mazda team, invited anyone to have a steer of the race car to see that the peripheral-ported 12A-engined RX-7 was indeed fair competition, and would not overrun the sport.

At a time when local drivers were going broke with hefty V8 bills, Moffat saw the Mazda as a reliable, cost-effective alternative – so much so that he believed Australian motor racing needed the Mazda. On debut, Moffat’s Mazda was three seconds off the pace, but he managed to win the ’81 Australian Endurance Championship only months later.

“The first real demonstration of its prowess came at the Sandown 400,” Moffat laughs. “We went the whole distance on one set of tyres. This showed how ideally balanced the car was. After our first stop there were sniggers along pit lane. People thought we’d forgotten to change tyres.”

By mid-’82, it was almost a forgone conclusion that the Moffat RX-7 would score pole at each round. At Lakeside in Queensland, Brock broke the lap record, but Moffat went out and clocked a lap 1.1sec better…

Moffat’s efforts placed the original RX-7 and the rotary firmly on the map in enthusiast’s minds. And it was the spark the engine needed.

The second-generation RX-7 (Series IV/V) was far more high-tech and re-introduced the 13B to Australia, but it lacked the race heritage of the original (and subsequent) generations. No dedicated Group A model meant no image-builders racing around circuits. But as a road car, it brought one very serious blow – a turbo version of the injected 13B.

Mazda had offered a turbo RX-7 (a 12A) in the first generation, but only domestically. With the second-gen, the boosted RX-7 was finally given a passport. The ’86 RX-7 Turbo knocked out 133kW/247Nm and sprinted to 100km/h in 7.8sec and down the standing quarter in under 16 – making it a quick car for the unleaded era. And the 146kW/265Nm Series V Turbo (1989) went a step further, nailing 0-100 in under seven seconds and the quarter in high-14s.

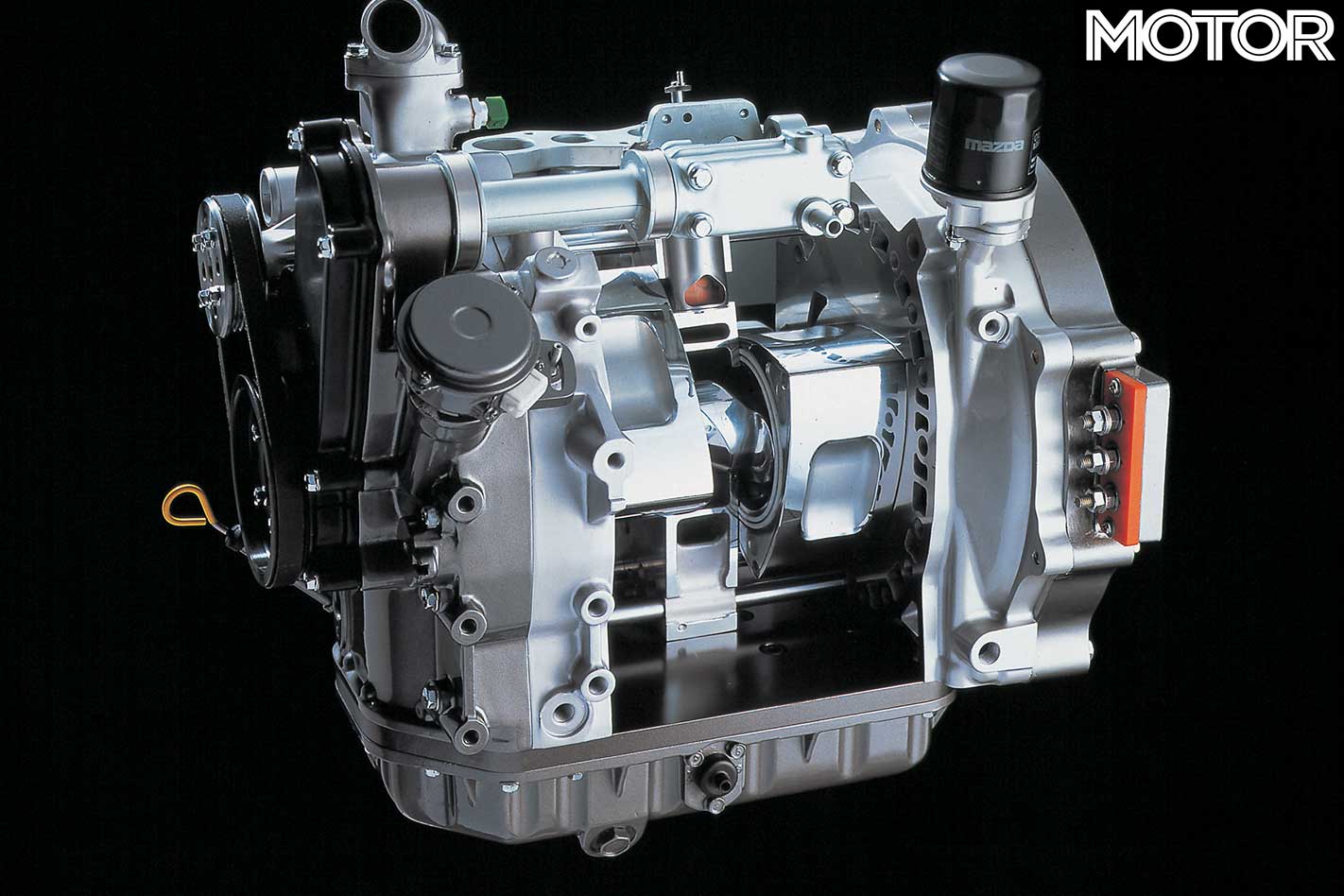

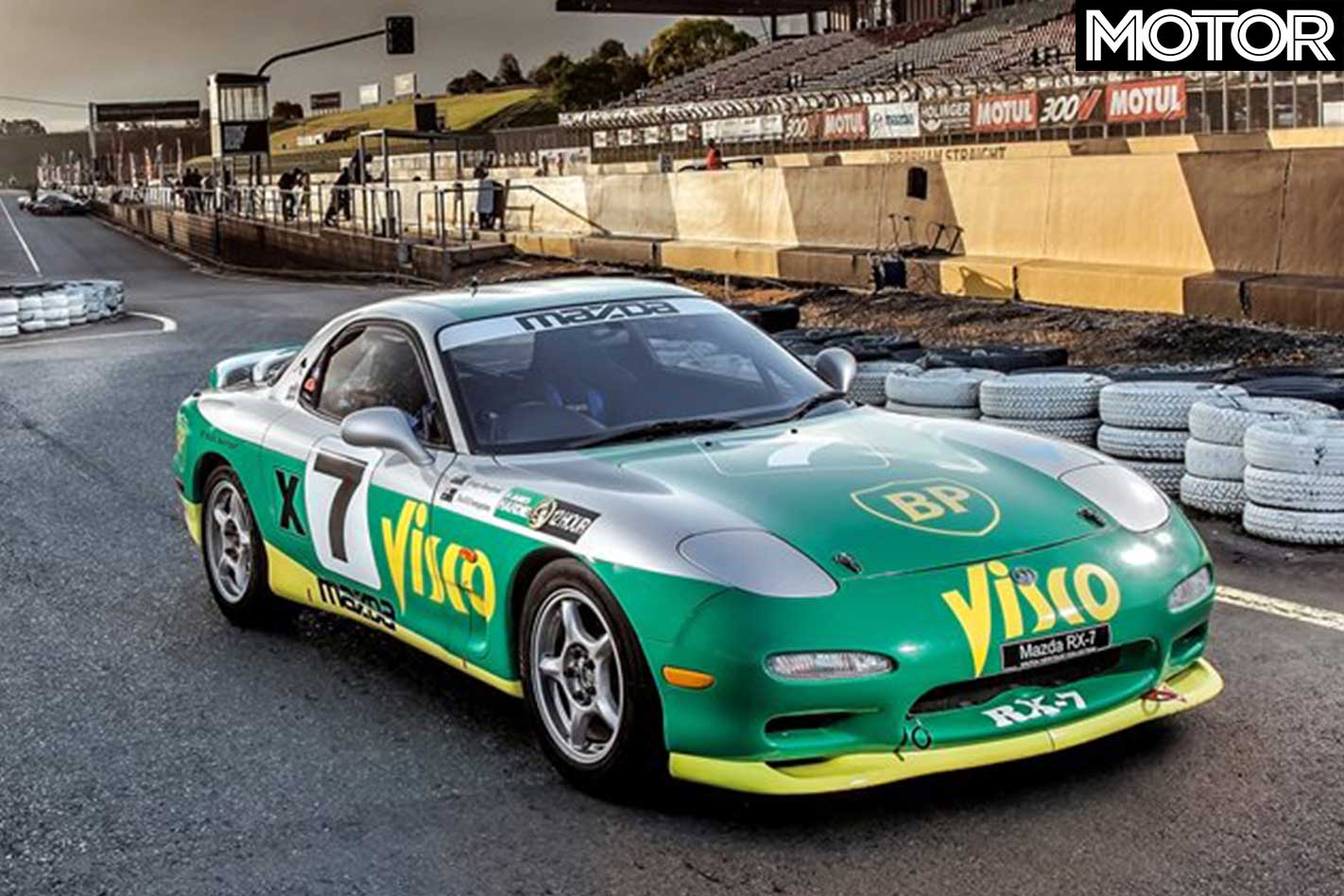

But it’s the third-generation RX-7 that became Mazda’s rotary rock star. Its 13B produced 176kW at 6500rpm and 294Nm at 5000rpm thanks to twin sequential turbos that eliminated low-rev lag, and extensive use of aluminium resulted in a car that weighed just 1290kg – some 80kg lighter than Honda’s all-aluminium NSX. It was also shorter, lower, wider, and had less overhang then the second-generation RX-7.

“This is a car you can balance on the throttle beautifully,” we said in June ’95. “Its chassis is great and it’s nicely weighted. Sharp rack-and-pinion steering, 50:50 weight distribution, wider track and lower centre-of-gravity all contribute to delightfully sporty dynamics.”

While it was the most expensive RX-7 ever offered ($99,750), its BMW M3R and 911 RS CS rivals were $190K and $218K respectively. Today, the legendary SP commands a resale value of more than double that of a regular RX-7, and it still holds the lap record for production cars at Mount Panorama more then a decade on.

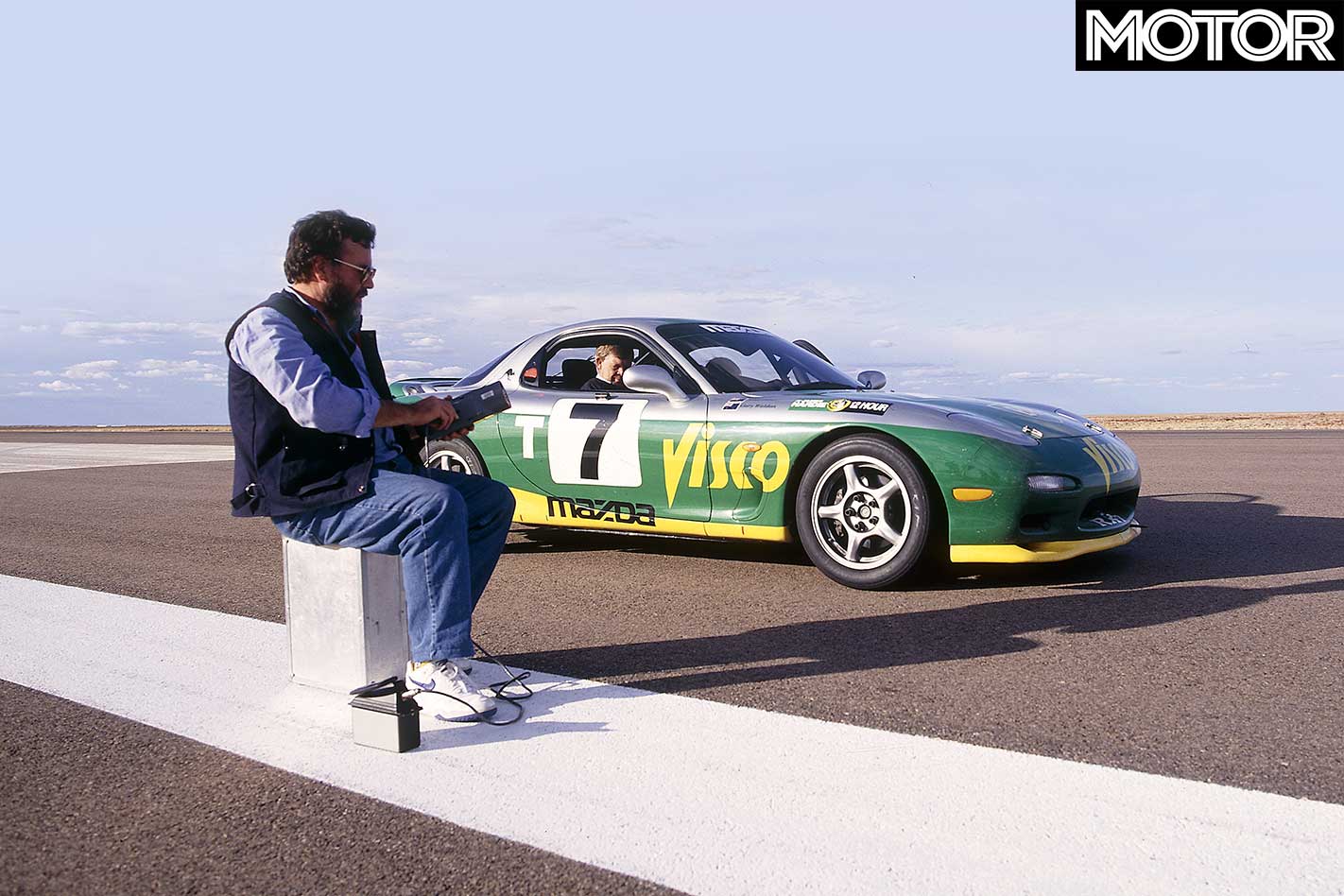

In June ’95, we wrote that the 204kW SP “picks up the ball where the standard RX-7 drops it and, in the right hands, will undoubtedly score racetrack goals.” And it did, with Dick Johnson/John Bowe winning the final 12-hour (at Eastern Creek in 1995) at Porsche’s expense.

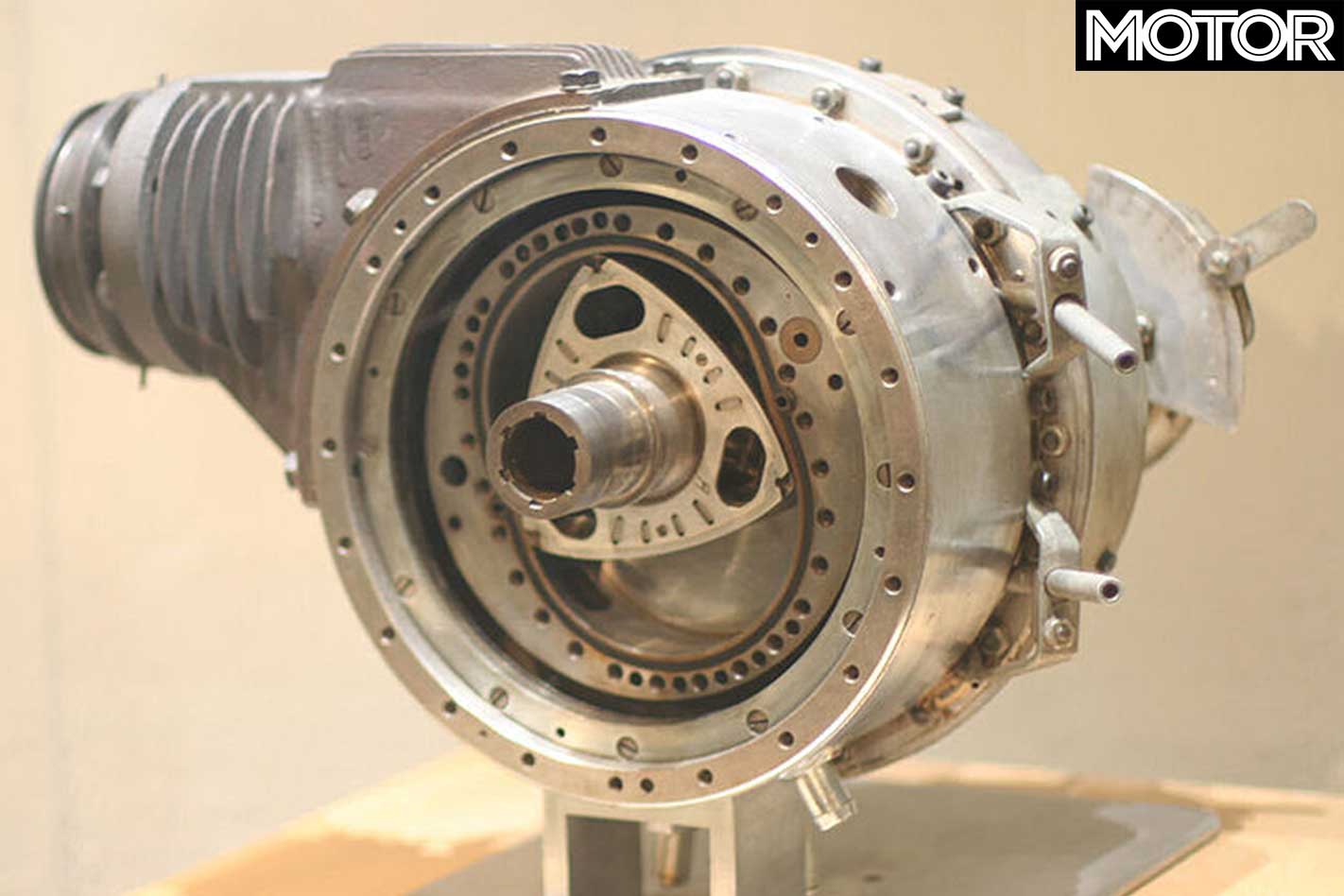

Biggest change to the RX-8’s 13B ‘Renesis’ was the repositioning of the exhaust ports, though weight was reduced by 11 percent over the RX-7’s 13B-REW. And it won the International Engine of the Year award in ’03 and ’04, beating the likes of BMW, Audi, Mercedes-Benz and Subaru.

The RX-7’s racetrack success, and even the Cosmo’s, proved the rotary’s speed and durability, and with wins at Daytona, Spa and Le Mans, its reputation remains solid. Mazda’s refusal to abandon an engine that has won such a cult following, despite its detractors, deserves praise.

But maybe the best is still yet to come for the rotary engine. Bring on next decade and the 16X.

The Future

The 16X – Mazda’s latest concept rotary – builds on the advantages of the RX-8’s 13B Renesis.

The 13B configuration has been around since the ’70s, so the 16X represents a major step towards assuring the rotary’s future.

Q&A: Allan Moffat

D: What made you think it’d be a competitive race car? AM: “The thing that impressed me most was that they [the test team] never lifted the bonnet. I was paranoid about keeping the engine going. I did maybe 40 or 50 laps and I said I was concerned about the engine, but the team let me do as many laps as I wanted. This really got my attention.”

D: What hurdles did you face for homologation? AM: “The biggest dilemma was why would I be interested in running a little thing with what was effectively two cylinders. What was the catch? Where were the other six cylinders? Allan Horsley said he’d fly the car from Seattle and offer anyone in the V8 fraternity to drive it. That was a pretty big thing. When it was approved, at the last minute, just to make sure, the Japanese homologated weight of 930kg was upped to 950kg. That 20kg was a noose around our neck the entire time we raced it.”

D: And without that extra weight? AM: “Well, as our swansong, we took the car to Daytona for the 24-hour in 1985. We took the 20kg out of the car, of course. There were 14 US teams there and I put the car on pole position. Gregg Hansford and Kevin Bartlett were there and said to me, “What did you do to it!?” and all I said was, “Funny what 20kg can do”. Whoever it was at CAMS that knew what that 20kg would do, I must thank them…”

Top Five – Mazda’s Rotary Racers

Q&A: Allan Horsley

D: What were the original RX-7’s strengths and weaknesses? AH: “We could set a lap time in it and just repeat it continuously. A lack of horsepower and torque were the real problems; a full tank of fuel would really punish the car.”

D: Fast foward a number of years, and you must be immensely proud of your Bathurst 12-hour success, particularly the locally developed RX-7 SP model? AH: “Well yes, I am. We developed the SP in such a short period. We heard the [Porsche] Clubsport and the BMW [M3R] were coming and thought that we weren’t going to win with the standard RX-7. So we started work on the SP. There were something like 180 changes, all made in the workshop at Kingsgrove. We had a great team put them together and we were incredibly lucky.

D: So what about a new RX-7? AH: “I’d love to see one…”

Other Rotary Engines