The little orange hatchback edges down the production line, sitting atop a metal jig. Yet to receive its headlights, wheels, engine, doors, or even interior, it’s but a naked body-in-white.

Looking down the production line, which inches forward slowly but unceasingly, there’s a queue of vehicles in a similar state – whites, oranges, blacks, blues and silvers. There’s the din of distant machines, the clack of far-off hammers, and giant ceiling fans the size of helicopter rotors circulate the hot air with a gentle artificial breeze.

Men, and the occasional woman, dressed in the same standard-issue blue overalls, move about the bare vehicles calmly and wordlessly, like they’ve done it a thousand times before.

Regardless of the location, there’s something endlessly positive about a new vehicle production line.

Cars being born, in their thousands, destined for excited new owners to serve faithfully – and to better their lives. Today, we’re at a ‘mega factory’, the largest new vehicle production facility in all of Asia – SAIC’s “brand new” Ningde plant in China.

While car factories in and of themselves are nothing special – hundreds exist all around the world – this one, opened in 2019, stands out as a sign of things to come. We’ve been granted rare access to witness China, the world’s factory floor, as it prepares to take on the global car market at its own game: making cars.

Until now, China’s local auto industry has been kept busy simply competing within its own domestic market.

With a population of 1.4 billion, think of it as if Holden were selling to 56 Australias, not just one. However, a post-COVID economic slowdown is pushing China’s automakers to export. Seemingly, producing fewer cars is not an option.

This isn’t necessarily a cause for concern. After all, China already manufactures half the items in your home; and if you purchase a new electric vehicle in 2023, even if it’s assembled somewhere like Japan, a significant portion will be made in China – possibly using a substantial amount of Australian raw materials.

Cars from China – setting aside the exceptionally fraught, often delinquent politics of the Chinese Communist Party – will be much more advanced, exciting and worthy of anticipation than you might imagine. After a six-hour train ride (at speeds up to 304km/h) we arrive in Ningde, Fujian Province, in the country’s sort-of-mid-south.

Travelling in China, whether along railways or motorways, they all feel as though they were built in the last decade. Astonishingly, China’s use of concrete every two years surpasses what the US used in the entirety of the 20th century. A true fact, believe it or not.

It’s with an odd sense of trepidation that we arrive at the factory itself on an oppressively hot day.

Travelling as a “journalist” in China, it felt as if I was reluctantly granted a visa, and the Chinese Consulate in Melbourne certainly gave me a sceptical grilling about my intentions.

Nevertheless, there I was, stepping into a state-owned, cutting-edge manufacturing facility as a camera-wielding Western journalist. “No foreign journalists have ever been in here,” says one of our hosts.

Before this enormous, 140,000 square-metre factory opened in September 2019, it was a “tidal flat” – a swamp. In just 17 months, it transformed from this into a state-of-the-art facility, churning out 63 vehicles an hour (see below).

This factory is owned by SAIC Motor, China’s largest car maker – the Toyota of China, to use a flawed analogy. SAIC, in turn, is owned by the Chinese state. Founded in 1955, the Shanghai Automotive Industry Corporation produces 5.37 million cars every year. A fair few of them end up in Australia, badged as MGs.

And yes, this is the same MG, theoretically, that started in England in 1930, producing open-top sports cars cherished by multiple generations of bearded men. Imagine the look on founder Cecil Kimber’s face if he were told that in 2023, an MG would be more likely to be a small electric hatchback made in Ningde, China.

Two young Chinese women greet us, dressed in tight blue dresses like they had just walked off a motor show stand. They are our tour guides.

We are handed earpieces for translating to English, and shown an excessively nationalistic video about the factory itself (thankfully, we are spared the eye-clamps).

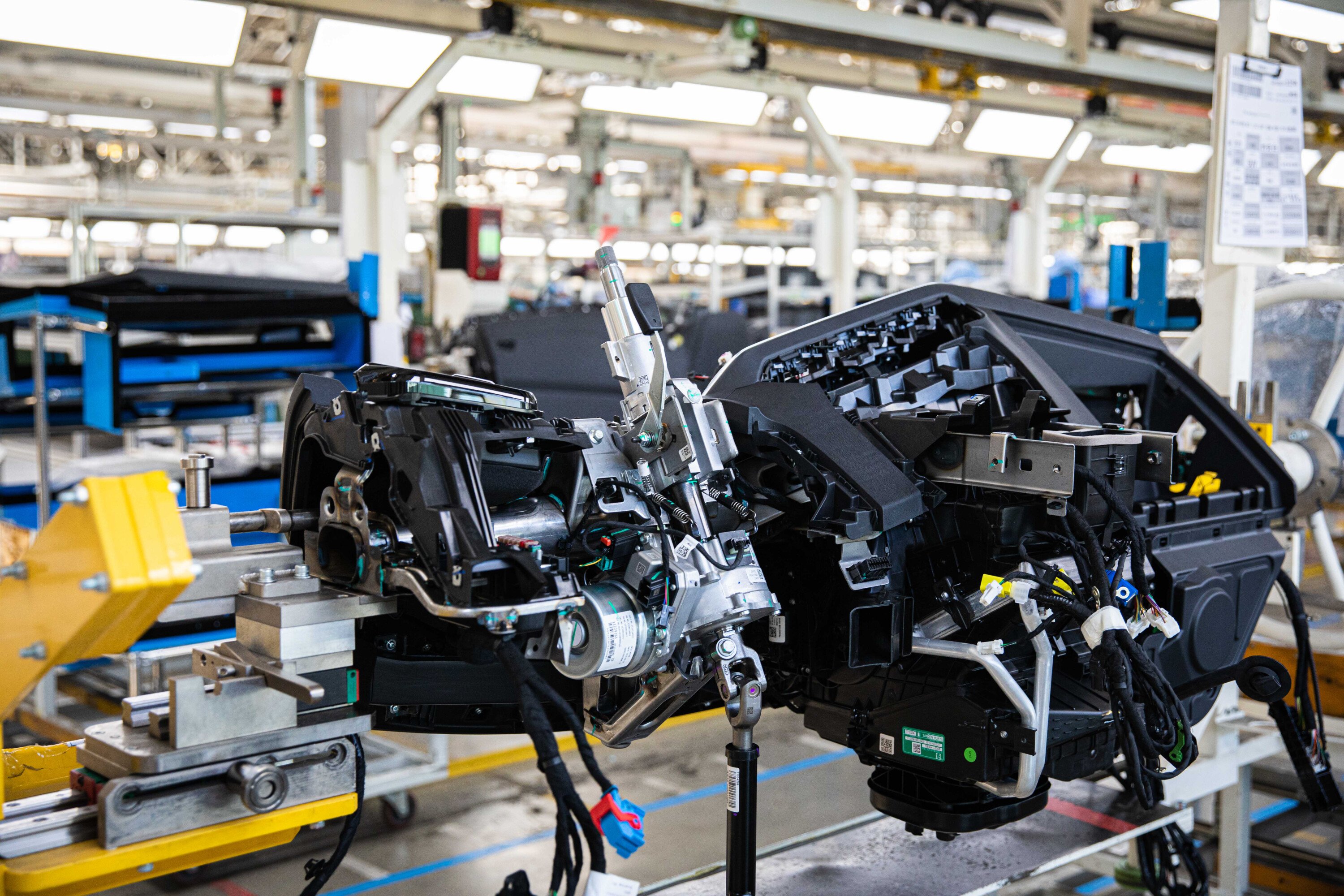

From a crisp, white, office-like foyer, two large grey doors open and we enter the factory floor. A strong smell of new plastics assaults our nostrils, and immediately there’s the low hum of an enormous factory at work – it’s as if we’ve stepped inside some gigantic organism.

The building itself is massive, and we are ushered straight to the most important part – the production line, which runs through the entire facility like a digestive tract.

While it’s nothing more than a giant, slow-moving conveyor belt, any car factory is something of a sacred place where metal, rubber, carpet and other raw materials go in, and out rolls cars – objects of affection that transcends nationalities, languages and politics. That’s exceptionally cool.

All sorts are on this production line, too. The one we are most interested in is the MG4 X-Power, the brand’s new all-electric, dual-motor hot hatch able to silently scurry from zero to 100km/h in a claimed, RS3-tormenting 3.8 seconds.

On this production line the MG4 cuts a somewhat more modern shape among MG5 sedans and HS SUVs, which both somehow look 10 years old, even though they’re brand new. There’s also the Clever – a tiny three-door microcar that’s not sold in Australia – and other cars under the domestic brand Roewe.

Those made for export are headed for the UK, Australia, New Zealand, Mexico and the Middle East.

More than 1500 people work here in two shifts – day and night – and save for a couple of breaks to scoff some sustenance, the production line never stops.

Curiously, it’s not a very loud place. All the time, there’s an odd, staccato, flute-like music echoing from speakers throughout the factory, like they’ve put a heavily sedated Willy Wonka in a corner somewhere with a keyboard. The music, however, is meant to communicate to the workers different stages of the day and production process – and they all know exactly what each tune means. But it lends the factory an almost ethereal feel.

We head into the more dimly lit “body shop” and the watchful eyes of those on the assembly line are replaced by encaged, highly choreographed machines.

There’s the smell of burning metal as teams of yellow-armed robots surgically bring together bare, pressed chassis bits.

Jets of sparks fly wildly as the familiar shape of a car comes together before our eyes. And unlike the humans, the 630 eyeless robots neither think nor feel, need breaks, or even realise we are in their midst. This makes the “body shop” a busy place, yet one in which you can easily feel a bit alone.

Even the robots eventually need breaks, however – every three months the production line is halted for a couple of days to recalibrate these highly accurate machines.

At one point, one of our hosts runs off in distress and attempts to block a bare chassis, located in an open area of the factory, from our camera-enabled phones, which are pointing and recording everything as if we’re spies.

The bare chassis cuts an unmistakeable, convertible, two-door sports car silhouette, a mix of Porsche and BMW Z4. “This is secret,” she says. “Do not take a photo”. With its sleek outline and creased haunches, this is the MG Cyberster – the Porsche-pursuing, all-electric sports car that will do 0-100km/h in 2.6 seconds.

Destined to nestle in among the MG sedans and SUVs on the Ningde production line, it will be rear-drive and all-wheel-drive, and many will board a boat for Australia.

There’s the faint smell of cigarettes as we move between tepidly cooled buildings in the stale heat. There’s a sense that the buildings had a fast birth.

Out a window we spot an orange MG4 X-Power motoring slowly around what looks like a mini racetrack. Every single car, we’re told, is driven on this 900-metre test track, up to 140km/h, to make sure everything works – straight off the production line, like a newborn foal needing to run mere moments after its first breaths.

After that, they are either loaded directly onto a train – that comes straight into the factory precinct – or a boat, thanks to a nearby roll-on, roll-off berth capable of exporting 300,000 cars each year.

As our tour ends, I’m left with the impression I’ve just seen a factory as modern as anything overseas – and to be sure, the Chinese have been making all sorts of things for a long time now. It will be fascinating to see how cars made in China change the automotive landscape in Australia.

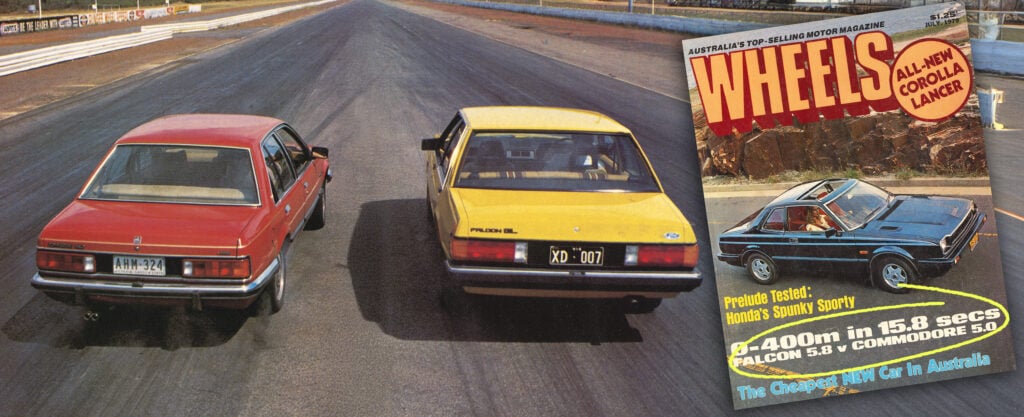

It was guessed that the rise of brands like Hyundai and its Excel would usher in a new era of cheap, disposable cars.

Today, however, Hyundai produces cars that are durable. While our consumption-driven society is only too happy to dump a broken flatscreen TV on the kerb for council collection, it’s hard to see the same happening for cars.

We’re too used to wanting to pay more for a car that lasts – a broken TV won’t potentially leave you stranded in the middle of nowhere – and cars made in China are only going to increase in quality, and cost.

Every car company, it seems, needs to have, and then grow from, its own kind of Excel. The Chinese, whose cars I wouldn’t say are poorly made (depending on the brand), will likely be no different. This is my guess anyway.

Much like the Excel, there’ll certainly soon be plenty of Chinese-made cars on Australian roads – pumped out from factories exactly like this.

5 of the worldu2019s biggest car factories

Ulsan, Hyundai, South Korea

Technically five plants combined, it can produce a whopping 1.5 million vehicles per year.

Manesar, Maruti Suzuki, India.

Pumps out up to 880,000 vehicles per year such as the Swift, Alto and Baleno.

Volkswagen Wolfsburg Plant, Germany.

Opened in 1938 by yes, those people… now produces up to 780,000 VWs per year.

Kentucky, Ford, USA.

Assembles around 750,000 vehicles per year, a most of them pick-up trucks like the F-150.

Tesla Gigafactory, Shanghai.

Around 710,000 Teslas come out of this factory annually, all of them electric. Impressive.

How China can turn a swamp into a functional car factory in 17 months

On April 27, 2018, the tiny aquatic creatures inhabiting an expansive tidal flat in Ningde, China, were blissfully unawares of the Fern Gully treatment they were about to receive.

The next day, a small battalion of bulldozers, excavators and tractors rolled in, reclaimed the sodden earth and began work on Asia’s largest new vehicle assembly line. Working day and night, what was normally a three-year process was condensed to just 17 months and on September 28, 2019, brand new MGs started rolling out the door in their thousands.

“Golden babies accelerate leapfrog development” is how SAIC’s somewhat propagandist promotional video describes the construction work.

There’s no denying, though, that China has something of a firehose it can point at construction problems, making them go away very, very quickly – as the Ningde factory demonstrates.

More EV stories to help you choose the best car for your needs

- ? EV news, reviews, advice & guides

- ❓ Short & sweet: Your EV questions answered

- ⚡ New EVs: Everything coming to Australia

- ? Australia’s EVs with the longest driving range

- ⚖️ Best-value EVs by driving range

- ? How much do EVs cost in Australia?

- ? How much more expensive are EVs?

- ⚖️ Number crunching: Is it time to switch to an EV?

- ♻ Should you buy a used EV?

- ?️ Are EVs more expensive to insure?

- ? Costs compared: Charging an EV vs fueling a car

- ? EV charging guide

- ? Are there enough EV chargers in Oz?

- ?? EV servicing explained

- ? EV battery types explained

- ? When do EV batteries need replacing?

- ? Hydrogen v EVs: What’s best for Oz?

- ? How sustainable are EVs, really?

MORE advice stories to help you with buying and owning a car

We recommend

-

Reviews

Reviews2023 MG4 XPower review: First overseas drive

China sets its sights on Australia's performance car market with 320kW MG4 XPower electric hot hatch – and it could be priced in the Golf R's ballpark

-

News

News2024 MG Cyberster: pricing confirmed, order books open

MG has revealed some Aussie details of its upcoming sportscar, including battery size and pricing

-

Reviews

Reviews2021 MG ZS EV review

Behind the wheel of MG's compact SUV EV