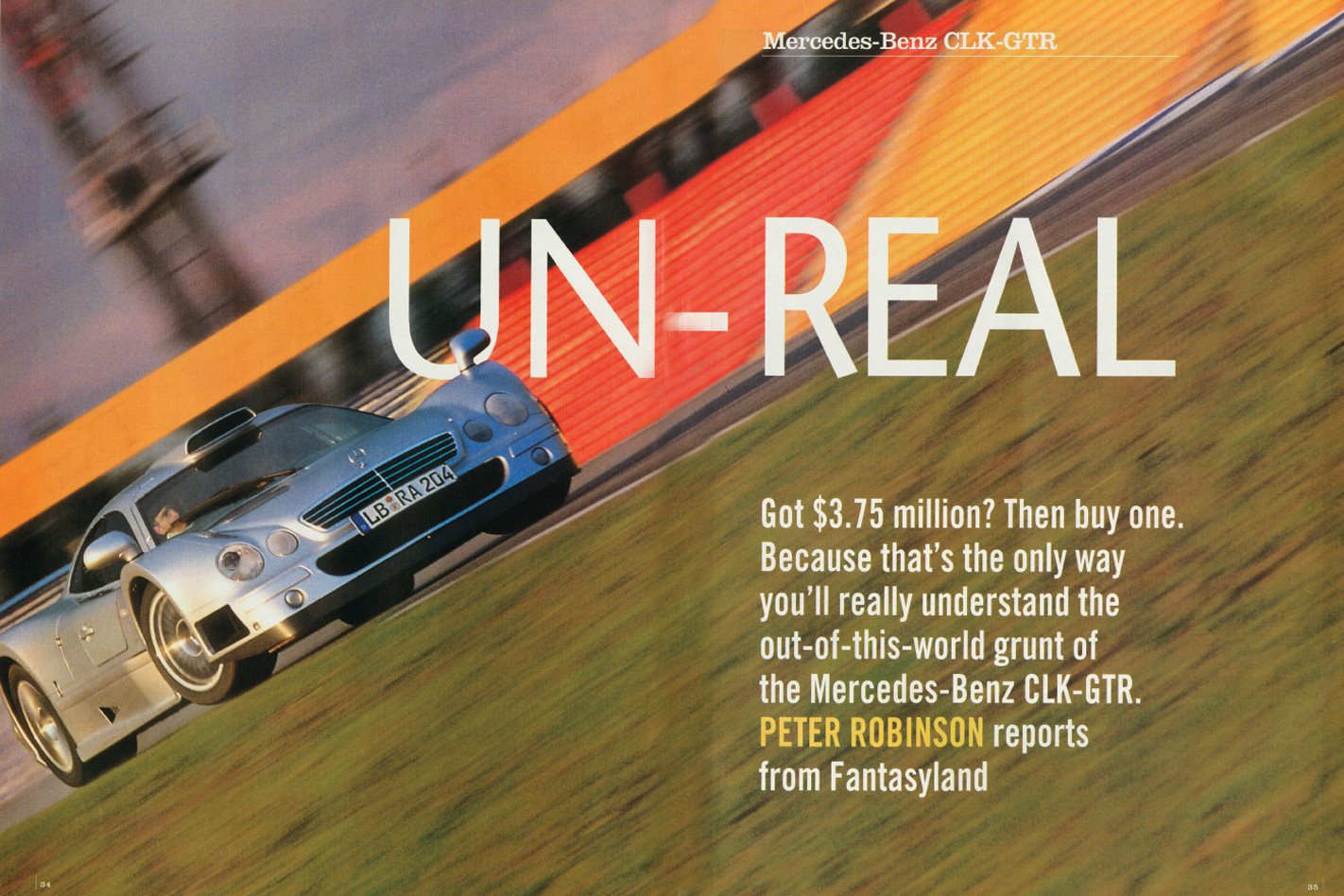

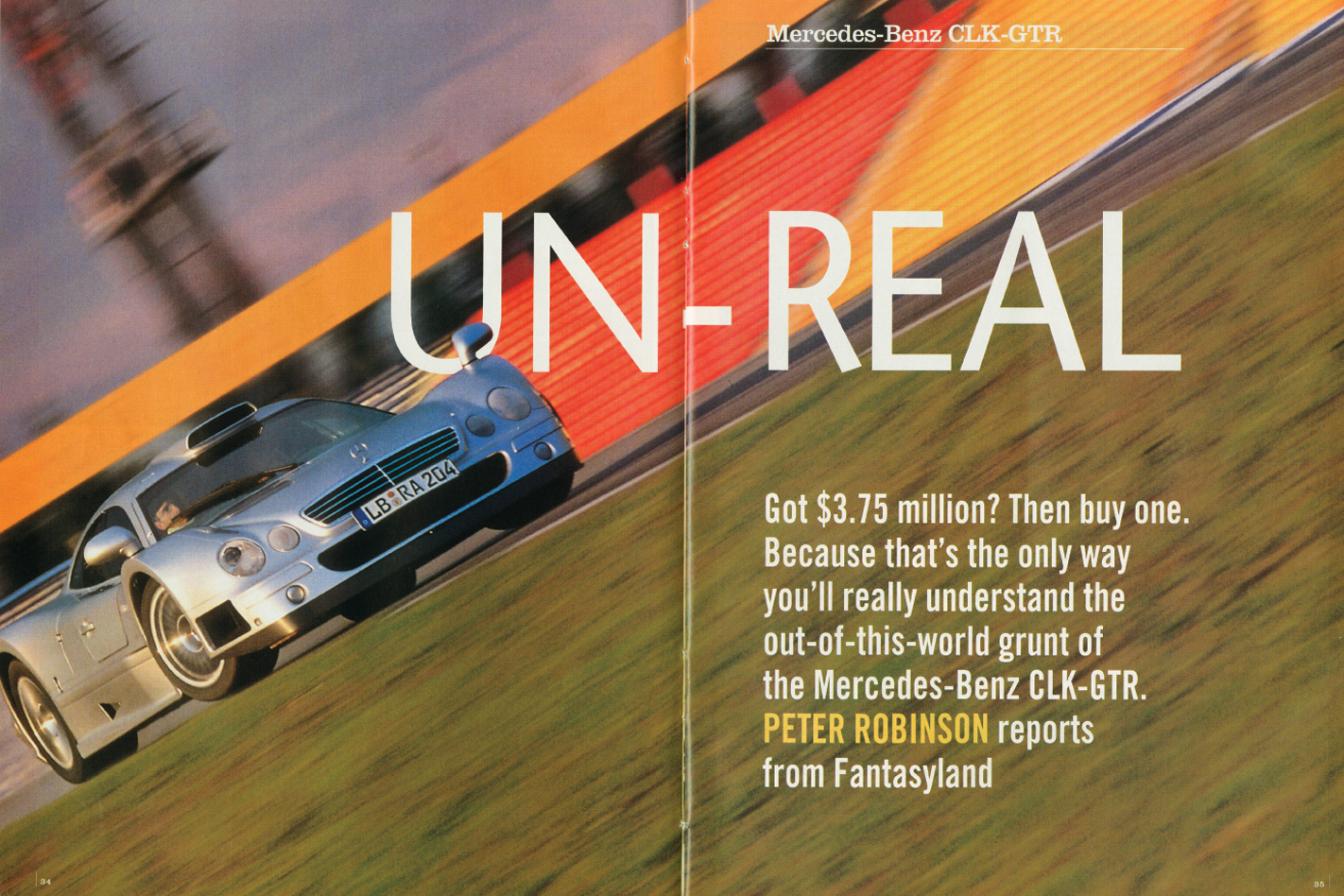

Got $3.75 million? Then buy one. Because that’s the only way you’ll really understand the out-of-this-world grunt of the Mercedes-Benz CLK-GTR.

This is real?

There isn’t space for a seat, not if my 1.92m frame hopes to move the pedals and turn the steering wheel. Steering wheel? Ah, that’s what’s missing. The mechanics have removed the airbag-equipped wheel to make threading legs, arms, and body across sills over a foot wide, and through the tiny opening created by scissor doors, possible.

You’re forced to twist and turn, like a screw top, before sliding your legs down into the diminutive foot well.

The wheel slots easily onto the spline, just like Mika’s McLaren-Mercedes MP4-13 or, more to the point, young Aussie Mark Webber‘s CLK-GTR GT championship car.

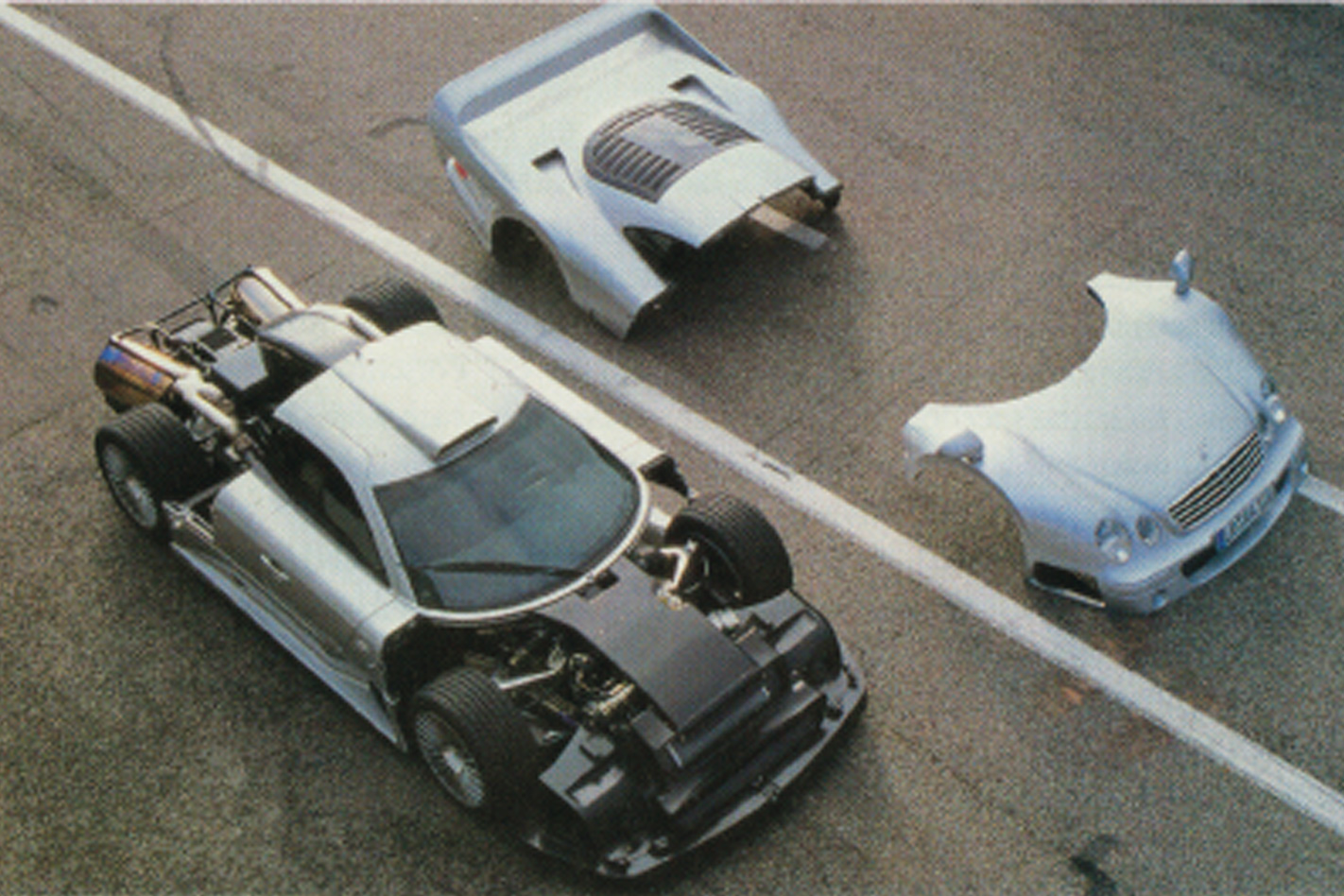

Everything looks Mercedes-familiar. The instruments are pure CLK, which means no oil pressure or oil temperature gauge. Talk about confidence. A small tacho is dominated by a bigger speedo. Still, it reads to 340km/h. Steering column stalks, air vents, air-conditioning, electric mirror, and light controls, even the sound system, are straight out of the Mercedes’ parts bin.

Maybe the links with a regular CLK are contrived, but they work in creating a perception that this stratospheric fantasy machine could only be a Mercedes-Benz.

Turn the very normal Mercedes key to fire up the mighty 6.8-litre V12 and it’s clear that behind the obvious visuals, the GTR is a pure racer, even if it doesn’t start by a button.

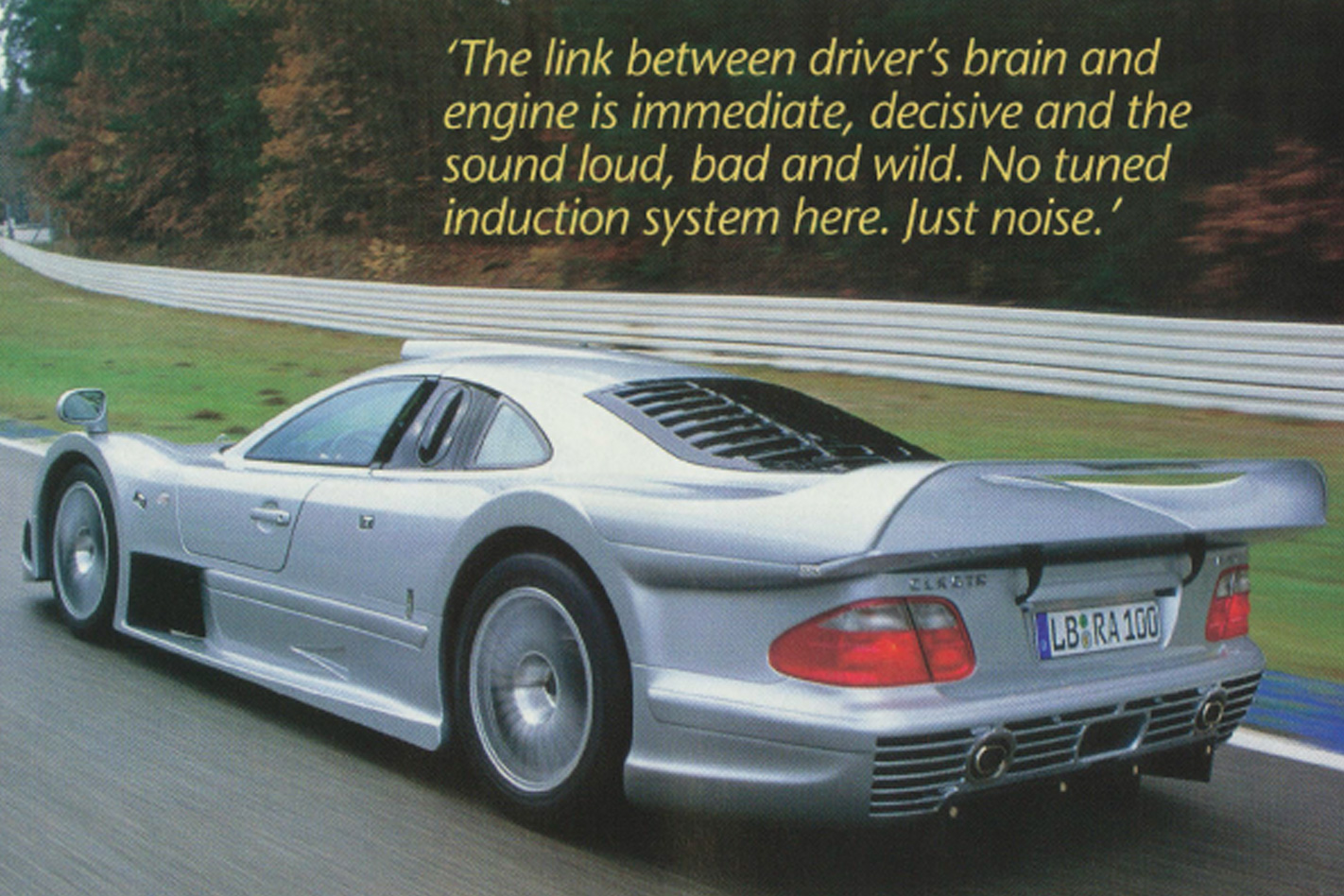

The link between driver’s brain and engine is immediate, decisive, and the sound is loud, bad, and wild. No tuned induction system here. No sonorous, musical exhaust note. Just noise.

Small chrome paddles behind the wheel work the six-speed competition Xtrac gearbox. The system looks identical to the F355 F1 Ferrari, except there’s a clutch pedal.

Strange, especially since the GTR racer uses a conventional centre gearshift. There are mutterings that the paddle shift exists on the road car because operating a normal gear shifter is virtually impossible in the cramped cabin. A green light in the speedo indicates neutral. Tap the right paddle back towards the wheel, remember to depress the clutch, and the electro-hydraulics select first.

This is not an easy car to drive gently. They call it a road car, but the GTR is not going to be happy coping with Toorak Road, or crawling through Double Bay on a Saturday evening. Bring the F50 instead and save the Mercedes for the autobahn or, better still, build your own circuit for private racing.

It’s about now you realise that there is no interior rear-view mirror, simply because, as with the GT Porsche 911, there is no rear window. For race safety and structural rigidity, the rear bulkhead/firewall connects floor with ceiling.

Short shift to second, up to third and the GTR is out of the Hockenheim pitlane. A short throttle travel only emphasises the engine’s responsiveness. Tickle the accelerator and the GTR instantly lunges forward. Push harder and it wants to spin the rear wheels – even with traction control containment.

The power figure makes the headlines, but really this engine is all about torque. Astonishing, breathtaking torque.

Mercedes stroked the production 6.0-litre V12 out to 6.8-litres. Now, it’s far closer to the 1997 FIA GTR racing engine than S600-silent. Despite softer cams, a reworked engine management system, and a full homologation four-catalyser exhaust, AMG swears the road GTR matches the power of the racer and has more torque.

The specs sheet says 450kW at 6800rpm and 775Nm at 5250rpm. Read peaky. For a more realistic guide to its potential you need to see the torque curve. At 2000rpm, the giant V12 pumps out over 620Nm of torque. The sheer range of torque is astonishing. It just keeps coming in an absurdly, wonderfully, vicious sweep. No need to change down, no point worrying about keeping the V12 high up in the rev range. There is so much urge, so much of the time that the gearbox is almost superfluous, unless you want to match competitive lap times.

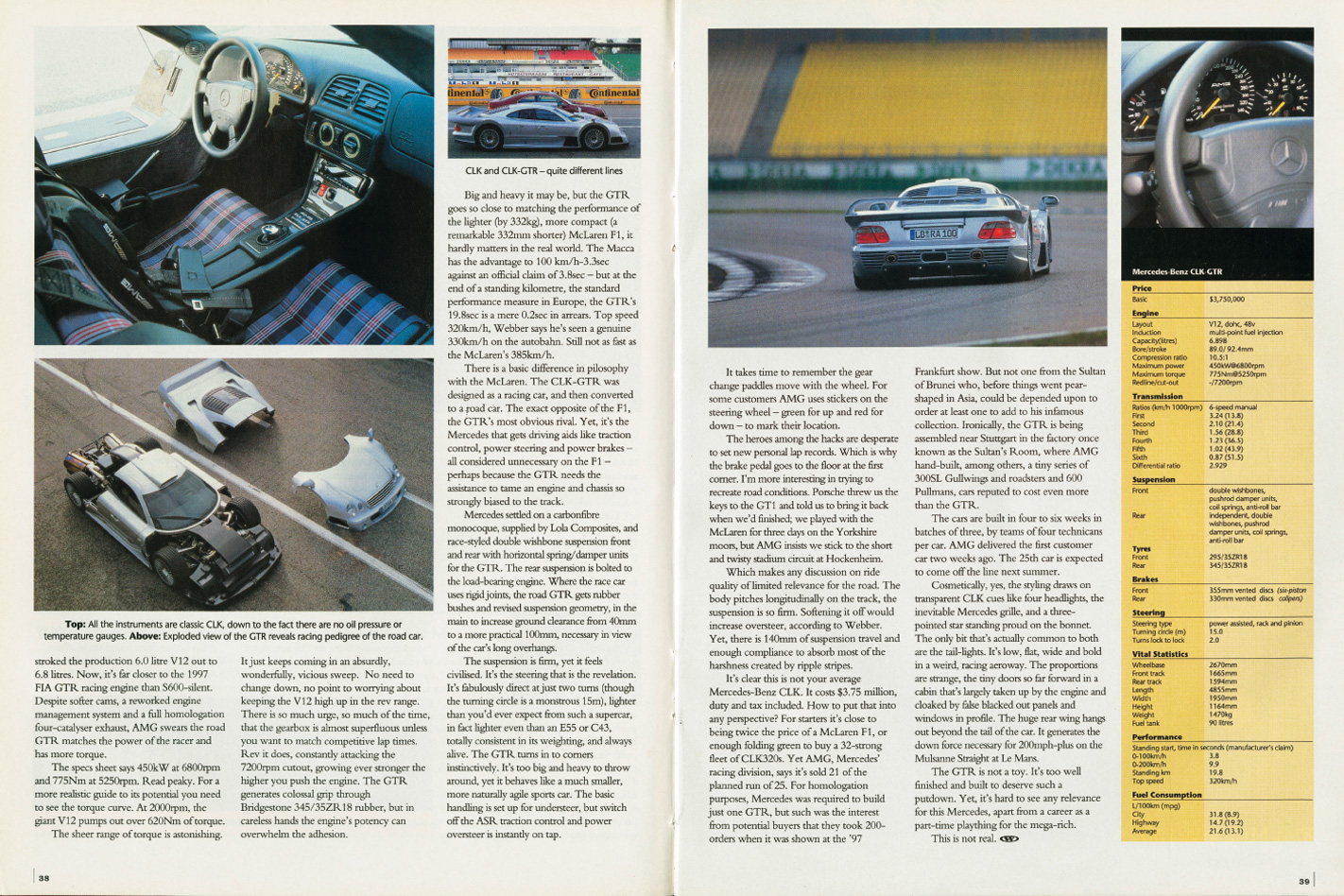

Big and heavy it may be, but the GTR gets so close to matching the performance of the lighter (by 332kg), more compact (a remarkable 332mm shorter) McLaren F1, it hardly matters in the real world. The Macca has the advantage to 100 km/h – 3.3sec against an official claim of 3.8sec – but at the end of a standing kilometre, the standard performance measure in Europe, the GTR’s 19.8sec is a mere 0.2sec in arrears. Top speed 320km/h, Webber says he’s seen a genuine 330km/h on the autobahn. Still, not as fast as the McLaren’s 385km/h.

There is a basic difference in philosophy with the McLaren. The CLK-GTR was designed as a racing car, and then converted to a road car. The exact opposite of the F1, the GTR’s most obvious rival.

Yet, it’s the Mercedes that gets driving aids like traction control, power steering, and powered brakes – all considered unnecessary on the F1 – perhaps because the GTR needs the assistance to tame an engine and chassis so strongly biased to the track. Mercedes settled on a carbonfibre monocoque, supplied by Lola Composites, and race-styled double wishbone suspension front and rear with horizontal spring/damper units for the GTR. The rear suspension is bolted to the load-bearing engine.

The GTR turns into corners instinctively. It’s too big and heavy to throw around, yet it behaves like a much smaller, more naturally agile sports car. Its basic handling is set up for understeer, but switch off the ASR traction control and power oversteer is instantly on tap. It takes time to remember the gear change paddles move with the wheel. For some customers, AMG uses stickers on the steering wheel – green for up and red for down – to mark their location.

The heroes among the hacks are desperate to set new personal lap records, which is why the brake pedal goes to the floor at the first corner. I’m more interested in trying to recreate road conditions.

Porsche threw us the keys to the GT1 and told us to bring it back when we’d finished; we played with the McLaren for three days on the Yorkshire moors, but AMG insists we stick to the short and twisty stadium circuit at Hockenheim, which makes any discussion on ride quality of limited relevance for the road.

It’s clear this is not your average Mercedes-Benz CLK. It costs $3.75 million, duty and tax included. How to put that into any perspective? For starters, it’s close to being twice the price of a McLaren F1, or enough folding green to buy a 32-strong fleet of CLK320s. Yet AMG, Mercedes’ racing division, says it’s sold 21 of its planned run of 25. For homologation purposes, Mercedes was required to build just one GTR, but such was the interest from potential buyers that they took 200-orders when it was shown at the ’97 Frankfurt show. But not one order from the Sultan of Brunei, who, before things went pear-shaped in Asia, could be depended upon to order at least one to add to his infamous collection.

Ironically, the GTR is being assembled near Stuttgart, in the factory once known as the Sultan’s Room, where AMG hand-built, among others, a tiny series of 300SL Gullwings and roadsters, and 600 Pullmans. Cars reputed to cost even more than the GTR.

The cars are built in four to six weeks in batches of three, by teams of four technicians per car. AMG delivered the first customer car two weeks ago. The 25th car is expected to come off the line next summer.

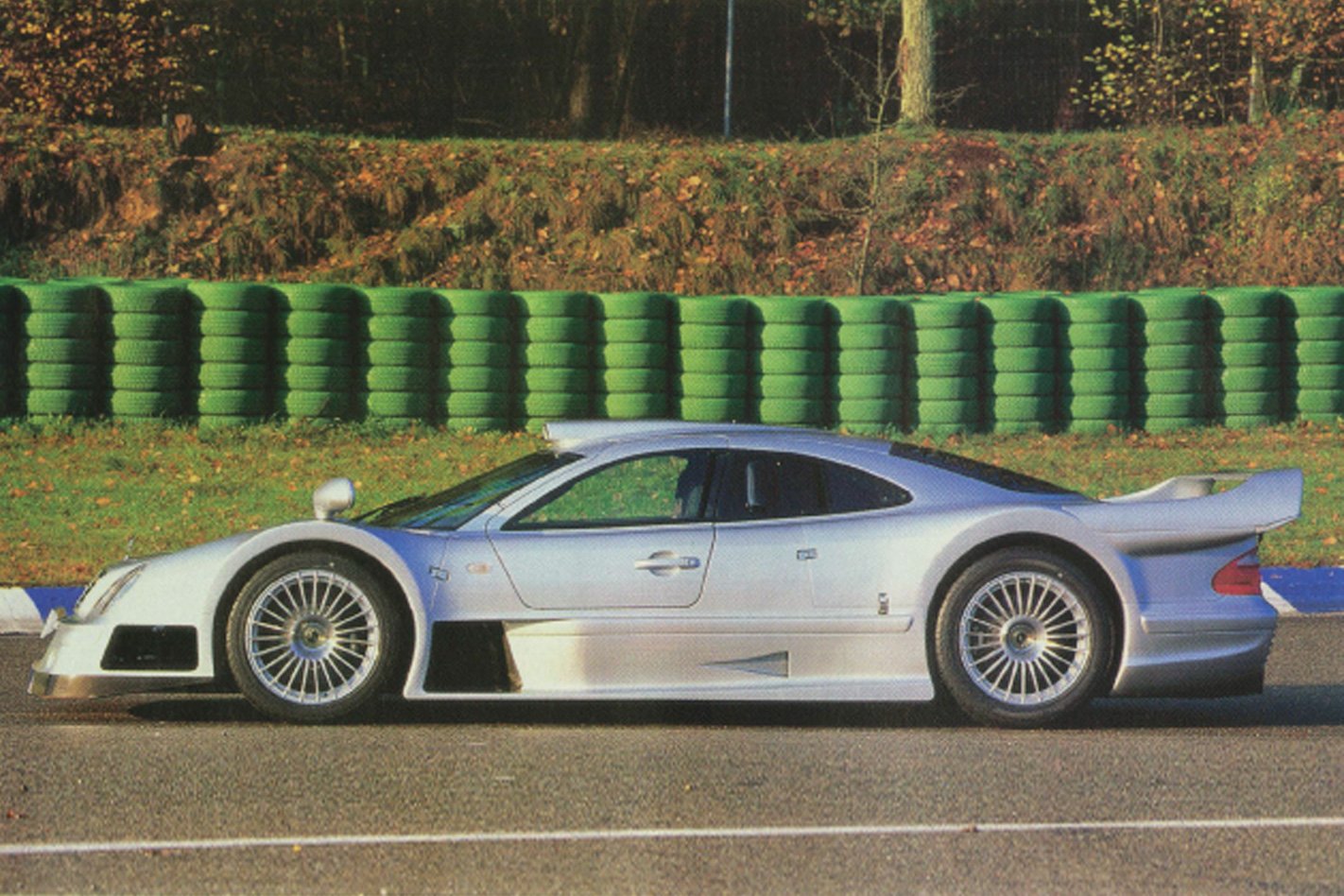

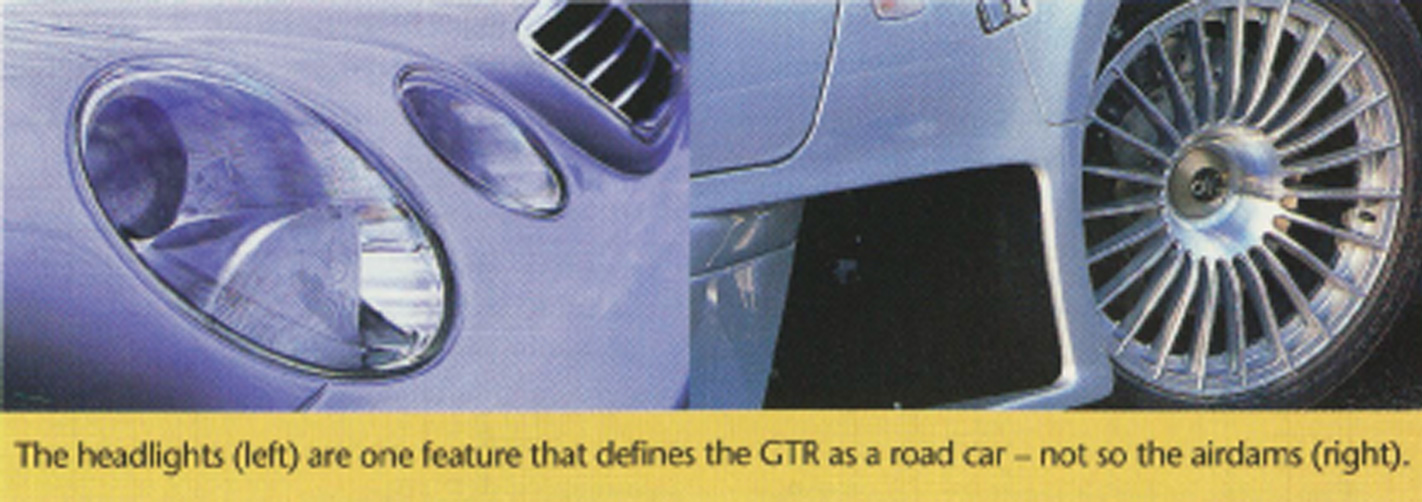

The proportions are strange, the tiny doors so far forward in a cabin that it’s largely taken up by the engine and cloaked by false blacked out panels and windows in profile. The huge rear wing hangs out beyond the tail of the car. It generates the down force necessary for 200mph-plus on the Mulsanne Straight at Le Mans.

The GTR is not a toy. It’s too well finished and built to deserve such a putdown. Yet, it’s hard to see any relevance for this Mercedes, apart from a career as a part-time plaything for the mega-rich.

This is not real.

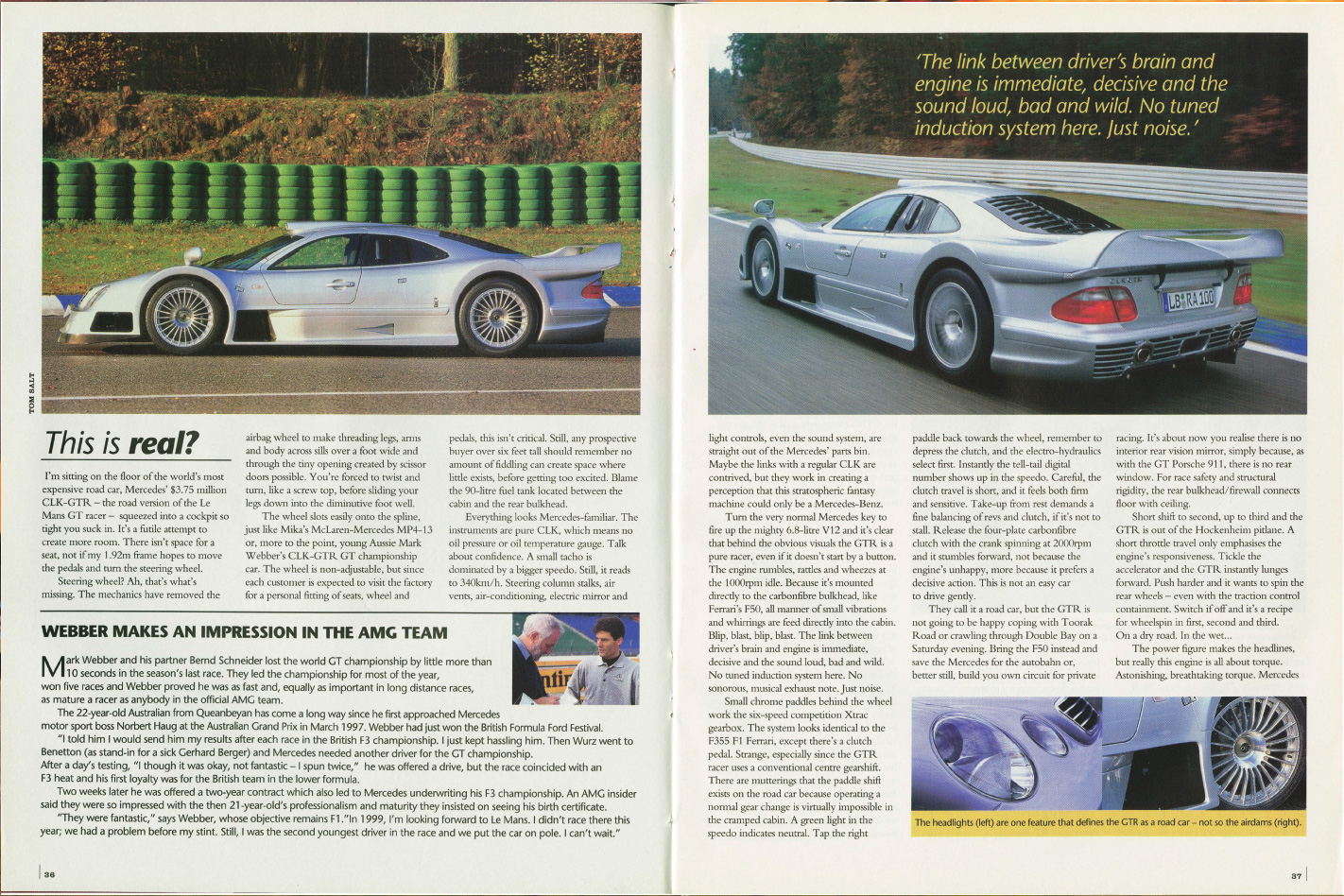

Webber makes an impression in the AMG team

Mark Webber and his partner Bernd Schneider lost the world GT championship by little more than 10 seconds in the 1998 season’s last race. They led the championship for most of the year, won five races, and Webber proved he was as fast and, equally as important in long distance races, as mature of a racer as anybody in the official AMG team.

The 22-year-old Australian from Queanbeyan has come a long way since he first approached Mercedes motor sport boss, Norbert Haug, at the Australian Grand Prix in March 1997. Webber had just won the British Formula Ford Festival.

“I told him I would send him my results after each race in the British F3 championship. I just kept hassling him. Then Wurz went to Benetton (as stand-in for a sick Gerhard Berger) and Mercedes needed another driver for the GT championship.

After a day’s testing, “I thought it was okay, not fantastic – I spun twice,” he was offered a drive, but the race coincided with an F3 heat and his first loyalty was for the British team in the lower formula.

Two weeks later, he was offered a two-year contract which also led to Mercedes underwriting his F3 championship. An AMG insider said they were so impressed with the then 21-year-old’s professionalism and maturity they insisted on seeing his birth certificate.

“They were fantastic,” says Webber, whose objective remains F1.

“In 1999, I’m looking forward to Le Mans. I didn’t race there this year; we had a problem before my stint. Still, I was the second youngest driver in the race and we put the car on pole. I can’t wait.”