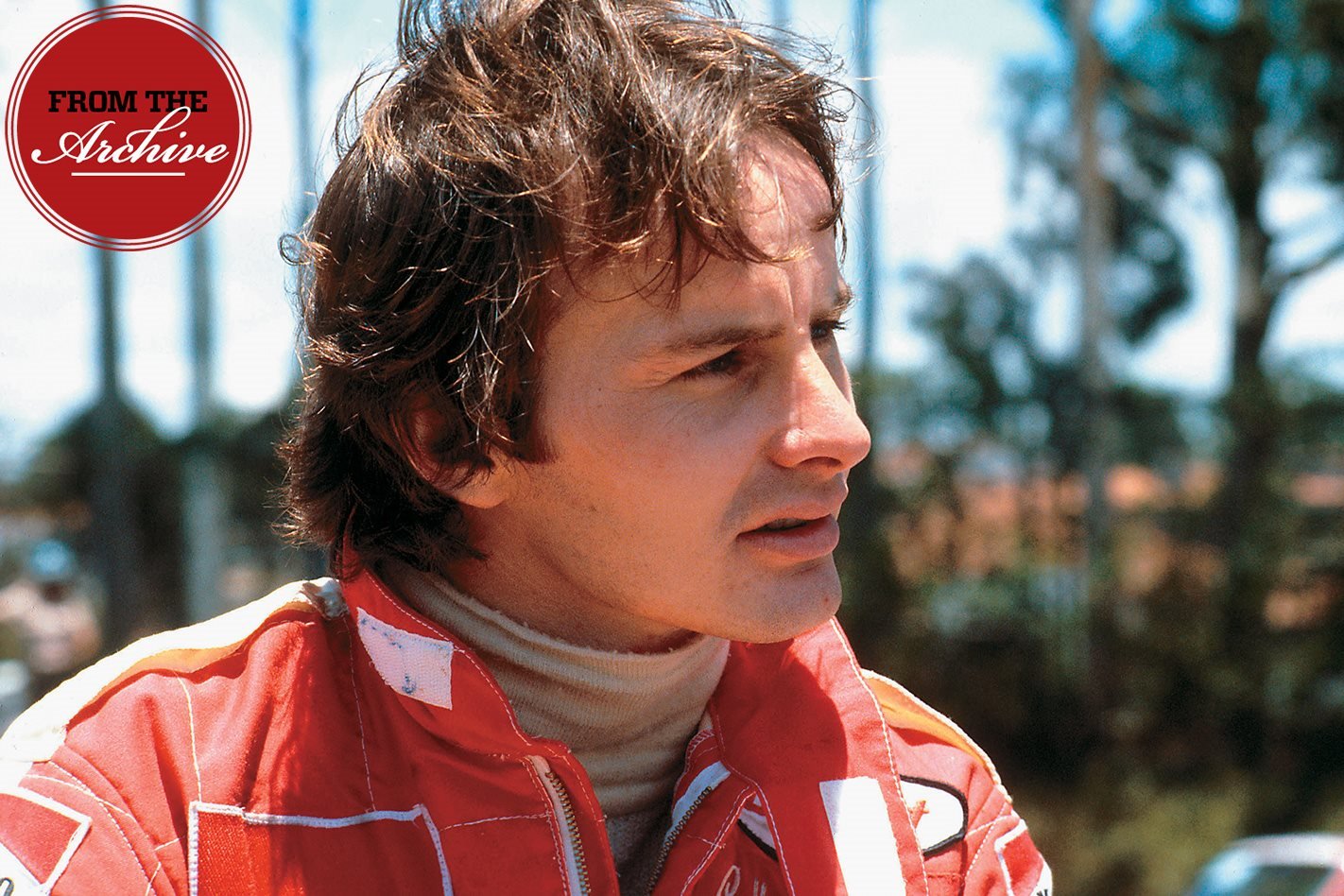

Motorsport lost a legend in 1982. Twenty years on, Gilles Villeneuve is remembered at the track where he achieved immortality.

First published in the August 2002 issue of Wheels magazine, Australia’s most experienced and most trusted car magazine since 1953.

May 9 is Ascension Day. Christians hold that, on this day, the crucified Jesus was carried in Elijah’s chariot, pulled by horses of fire, in a whirlwind to the Throne of God. Ascension Day symbolises Jesus’ departure from his human limitations, and his arrival in the eternal life of the gospels.

On May 8, 2002, I stood in a Belgian forest, alone but for the tall trees, looking across 11 metres of lonely asphalt. Exactly 20 years earlier, in the final 10 minutes of qualifying for the Belgian Grand Prix, Gilles Villeneuve’s Ferrari 126C2 had howled past the pits about half a kilometre behind me, passing the ‘In’ board held out by Ferrari F1 team manager, Mauro Forghieri.

At 1:52pm, travelling at some 225 km/h down the hill to my left, the Ferrari clipped the rear wheel of Jochen Mass’s cruising March. In the ensuing whirlwind that took place right in front of where I now stood, the great French-Canadian – the last true Ferrari driver, the last racer’s racer, a 32-year-old bloke with two young kids – began his eternal journey.

Twenty years ago, I heard the silence, felt the blackness in my gut, across a space as wide as the world.

It was a big year for me, too: In February of that year, aged almost- 19-and-a-half, I had started a career in journalism on Racing Car News magazine. One of my jobs was to write grand prix reports (though it was another three years before I went to a GP), by taking notes from the television broadcast, then filching details from the European magazines that arrived two Tuesdays later.

Having only a black and white TV myself, I was compelled to regularly ask a tall, fair-skinned girl named Virginia, with black hair and dark eyes, if I could watch GPs late at night in her apartment in Coogee. No trouble, she said: she had no interest in Formula One, and even less in me.

I honestly can’t remember if I heard about Villeneuve’s crash during Sunday, or whether I saw the footage a few hours before the Belgian GP telecast, on the six o’clock news. Certainly, it was on Virginia’s television, in her ground-floor flat, with the yellow lounge chairs and the brown bean bag and a cat whose name I forget.

Zolder is about 70km east of Brussels, in the Limburg province, at exit 27 on the E314. The circuit is set amid stands of pine trees, whose slender, tan trunks and yellow-green foliage have an almost luminous quality under the Euro-grey sky. The pretty, rural 4.0km circuit hosted its last F1 grand prix in 1984. That race, somehow fittingly now, was won in Ferrari number 27, by Michele Alboreto.

Driving out from Brussels, you pass the turnoff to the town of Leuven. It was to a hospital in Leuven that Villeneuve was taken by helicopter, just 11 minutes after the crash. He was artificially kept alive until his wife, Joann, could be brought from Monaco, where she and their two children – Jacques (11) and Melanie (8) – had remained for Melanie’s holy communion that day.

Eerily, this was the first grand prix that the Villeneuves hadn’t attended together as a family.

I had stopped the previous day in Leuven, at the giant UZ Gasthuisberg hospital on the hill, to ask if that’s where Gilles Villeneuve had been brought. It’s one of three hospitals in Leuven, all within two kilometres of each other. None of the reception staff had heard of Gilles Villeneuve; well, they weren’t working here 20 years ago. In any case, it was explained to me at each hospital, they’re not allowed to divulge patients’ records.

stayed.”‘ At which, she stifled a laugh: “Madonna? In Leuven?”

“My past is scarred with grief … father, mother, brother, sister, wife … my life is full of sad memories. I look back and I see my loved ones … and among my loved ones I see the face of this great man: Gilles Villeneuve.” – Enzo Ferrari

Only one Ferrari, a gunmetal-grey 500 Maranello on Belgian plates, passed me on the long, sooty motorway to Zolder. When I arrived at 11 o’clock, the circuit was clearing up the clutter from the previous weekend’s DTM German Touring Car round, but my eye was caught by a yellow poster that read: ‘Ceremony – Memorial Gilles Villeneuve 1982-2002.’

“Who will show up, we will see at 12 o’clock,” shrugged Walter Goossens, Zolder’s friendly and enthusiastic marketing manager, who explained that the circuit and two Belgian Ferrari clubs had organised a small commemorative service. It would include the unveiling of a new memorial plaque at the site of the crash, long since named the Gilles Villeneuve chicane. (Canada’s GP circuit in Montreal, and a corner at lmola where Villeneuve totalled his Ferrari in 1981 without suffering a scratch, are also named after him).

Along with the 50-odd car club people who did turn up, we just had to wait until midday, when the driver training classes paused for lunch, before we could walk over there. I found the guy in the reddest-looking Ferrari jacket and introduced myself. He was Giulio Giulietti, secretary of the Ferrari Club Genk. He was here. Not just now. Back then.

“After some minutes, the security gave us more information, and we knew very quickly that it was very bad … We knew by 3.00pm that Gilles was dead, but you can’t make the announcement of these things.”

The clubs, and Zolder circuit, had invited Jacques Villeneuve today. Nobody had expected him to come, but he had at least replied. “He isn’t involved because he has his way of life,” Giulietti said. “He doesn’t want too be remembered as the son of Gilles, he has his own life to go.”

Zolder had, in 1984, erected a monument to Villeneuve in the pit lane – a monolith of marble, with Gilles’ helmet and a small statue encased in glass. It was, however, removed by the previous circuit management in 1995. lts major elements are now in the private museum of long-time Belgian Ferrari distributor Jacques Swatters.

‘The new management missed the statue of Villeneuve,” Goossens said. “So we have decided, 20 years after, to install a new monument, a new memorial plate. This will be kept in honour, together with a new monument we will unveil at a Gilles Villeneuve Memorial race meeting in June (22-23). It will be a life-sized artwork, based on the characteristics of Gilles Villeneuve, that will be placed in the paddock area so that all the people can see it there.”

Trevor and Jacquie Green had left Milton Keynes (“it’s near Silverstone!”) at sparrow’s this morning, and were driving back this afternoon. That made it three visitors who weren’t members of the Genk or Charleroi Ferrari Clubs. Mind you, both clubs seem to suffer a paucity of actual Ferraris; the only exotica in the otherwise unremarkable car park were a new 360 Modena, a weathered 328 GTS and an Alfa Romeo SZ ‘Mostro’.

Jacquie wore a T-shirt bearing the image of Gilles’ helmet. The Greens, late-30ish, had hearts that were pure. “We came here just to pay our respects to the guy,” Trevor said. “He meant a lot to us when we first started watching F1, basically he brought us both into F1 … he’s a long time gone, but everyone still remembers him.

“I mean, Gilles made F1 for five seasons. You look at those years – when he started in 1978, he blew people away in a McLaren that was three years old… He sat in a car that James Hunt couldn’t drive, and he drove it around Silverstone and blew ’em away… The guy never gave up.”

What were you two expecting to find here today? Jacquie: “I wasn’t sure whether there’d be thousands here or maybe, 10. One or the other.”

Trevor: “When we got hold of Walter, and he said there’d be a small press conference, then we walk over and dedicate the new memorial, I thought, ‘Great.’ That’s all you really want. Some recognition of what the guy really was, and what he held up.”

Just after midday, we tailed Goossens and the group of car club people to the back of the pits, entering the circuit at the back chicane. We walked up a gentle rise, the pedestrian bridge spanning its crest, and suddenly the line of the trees and the land gently falling away just-so and the stupidly thin-looking ribbon of track spilling fast and down and away to my left … immediately I knew it, and now I saw it as he had seen it.

My stomach sank, standing there, as I understood that all the algorithms in the world probably would not have delivered a different outcome from the one we got on May 8, 1982. Thirty metres before or after – half-a-second at 225 km/h – there would have been a right and a wrong. But the two cars’ trajectories coincided precisely where, for both drivers, the choices of moving left or right are equally valid.

Both moved right.

I watched them unveil the memorial plaque, a subdued affair in dark, polished granite, and saw the accountants and salesmen and lawyers and tyre retailers pose for photos and give three cheers for a man, a brave and gifted man, they were claiming as a lost brother.

But then , what was I doing there , if not to own some of his glory?

By 1.00pm, all the Michael Marlboro merchandise had wandered off to the catered lunch organised in the conference centre. I had no place special to be; on May 8, certainly no place more special than here. Disturbed by nothing but the sound of wind, and the dark vision of a Ferrari climbing into the air, I crossed the track before the driving school cars came out, and I waited.

At 1.52pm on May 8, 2002, at the site of the crash that claimed one of the most gifted and loved drivers in Formula One history, there was just one person. I suppose I’d hoped it would be like this. I had leaned against the Armco fence by the woods, pondering the 32-year-old man’s death, honestly hoping to feel something special other than respectful sadness – hoping to be touched by a spirit.

Instead, I heard a noise behind me and turned around to face … me. Taller, fairer-skinned, but the man who had appeared through the trees and had paused there, looking back at me, was of a similar age, similar build, similarly balding – and similarly, here at this place and time.

Armand, an IT technician, had taken the day off work to drive down from his home in northern Holland. In 1982, when he was 17, he lived in Maastricht, just half an hour away. And on May 7 that year, he was here.

“I saw him on the Friday, for the last time … Saturday, we couldn’t go because my father was ill, but I saw it on TV. I was quite shocked, I tried to come here as quickly as possible, but it was too late.”

Armand has come back on every fifth anniversary since, always at 1.52pm. He thanked me for being there. “The last time I was here, I hung up a Canadian flag, but there was no-one else. I have been a few times, and I was always alone. That’s Formula One – they forget the whole thing…

“I have a lso been in Berthierville (Quebec), especially to the Gilles

Villeneuve museum, and to visit his grave. I think it’s an empty grave,

in Berthierville. I think he was cremated and Joann has the ashes, but they still have a grave for him. But you have to search for it, and the grave of him is next to a factory, so it’s very sad.”

Armand was happy to hear that, at Zolder, Gilles had a new monument, one that was promised to last for years and be cared for and respected. He said he thought there were now two generations of Formula One fans. I said there were probably about 10, each united by a driver – Fangio, Clark, Lauda, Senna – who dominated and defined their era.

For two strangers from opposite sides of the planet, Gilles Villeneuve had captured a time, a place, a mood. Coming to Zolder, we realised, had been about celebrating a life that is unique and irreplaceable: One’s own.

Laps of a racing god

Five races that made Gilles Villeneuve a legend

TROIS RIVIERES FORMULA ATLANTIC 1976

As far as the few in Fl who had even heard of him were concerned, Gilles Villeneuve was a hick in an outback championship. Then, at the tail end of 1976, world champion elect James Hunt guested in the North American Atlantic Series’ big event- as team-mate to the Crazy Canuk who had won virtually every race that year. Hunt tested and practised hard, and was second quickest. But still 0.5 seconds off Villeneuve. Hunt requested that they might swap cars for the next session. They did. This time Gilles was 0.8 seconds quicker. He won the race, too, start to finish. Hunt went back to Mclaren and told ’em he’d just found the fastest guy he’d ever seen.

ZANDVOORT 1979

A three-wheeled wrecker, shredding rubber, then sparks, then whole chunks of wheel rim as Gilles’ flat-refusal to concede defeat ever overruns ‘game-over’ reality.

His crazy ride back to the pits has become a freeze-frame moment encapsulating the man’s spirit. Some have also sought to use it to tag him a rock ape. But that’s to misunderstand the image. The Ferrari became damaged not through driver error, but from a tyre blow-out that spun him out of the lead. A lead, what’s more, that he’d taken from Alan Jones’ Williams – a more modern car with heaps more downforce – by passing him round the outside of Tarzan corner!

WATKINS GLEN 1979

A drizzly Autumn day in New York state was the backdrop as Gilles again engaged Alan Jones’ faster Williams in unlikely battle. Their duel took them a whole lap clear of the field. As the track then dried, Gilles stopped for slicks and caught Jones so fast that Williams called their man in for a tyre change, too – then forgot to bolt up one of his rear wheels, leaving Jones ditched at the end of the pit lane. With more than 30 laps still to go, Villeneuve’s oil pressure began to drop alarmingly. He eased back, allowed others to unlap themselves, and sweetly nursed that baby home to victory. He could be velvet as well as brimstone.

MONACO 1981

lt was still early days for the turbos – they had only around 100 horsepower (75kW) advantage over a normally aspirated Cosworth DFV, but with the penalty of throttle lag – very bad news round the tight twists of Monte Carlo. Besides, the Ferrari chassis was woeful. Subsequent designer Harvey Postlethwaite later reckoned it had literally a quarter of the downforce of a Williams or Brabham. Didier Pironi, then one of the world’s very fastest drivers, qualified his 18th. So what was Villeneuve doing on the front row, outqualified by mere hundredths of a second by Nelson Piquet in an illegally light Brabham? Forget that Gilles then won the race. The miracle happened on Saturday.

JARAMA 1981

From seventh on the grid in a dog of a Ferrari he used to call his big red Cadillac, Gilles was second into the first corner.

Then Alan Jones spun out. All Gilles had to do now was hold five faster cars behind him for the full distance in a bucking bronco of a machine that was just aching to spit him into the gravel. Remarkably, he did just that. Not one single mistake, not a missed apex or locked wheel to allow in the tiniest bit of daylight. Victory in a car that should have struggled to make the top 10.

MARK HUGHES